Sea Level Rise and Coastal Risk

- Global Sea Level Change

- Historical Trends in Sea Levels

- Sea Level Rise Projections

- Sea Level Rise Impacts

Download page in PDF format or read below.

or read below.

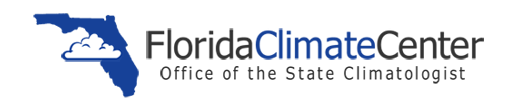

Florida is among the most exposed states in the country to sea level rise and coastal storms. With its low-lying coastal topography and more than 8,400 miles of shoreline, much of Florida and its coastal population are vulnerable to the impacts of rising sea levels. While vulnerability to sea level rise varies considerably across the state, with many inland areas at much higher elevations, sea level rise impacts will not be restricted to areas along the immediate coast.

Figure 1. Composite Digital Elevation Model (DEM) of Florida, in feet NAVD88. Source: South Florida Regional Council report (2016).

Global Sea Level Change

Global mean sea level rose rapidly following the last ice age approximately 20,000 years ago. However, the rate of sea level rise slowed and has been nearly stable over the last few thousand years. Since around 1900, global average sea level has risen by about 7-8 inches (Hayhoe et al. 2018, NCA4) and the rate of sea level rise has been accelerating in recent decades as ocean temperatures warm. Nearly half of this rise in sea levels has occurred since 1993, and the rate of global mean level rise since 1993 has been approximately 3.4 mm per year. It is virtually certain that global mean sea levels will continue to rise throughout the 21st century and beyond.

The main contributors to changes in global mean sea level are thermal expansion caused by warming ocean temperatures, melting of land-based ice that results in the addition of fresh water into the ocean, and local land water storage (e.g., water that is pumped from land or impounded by dams or other structures). Sea level rise can vary across the coast due to ocean currents and tidal fluctuations.

Data on sea level changes come from multiple sources, primarily from tide gauges, coastal buoys, and satellite altimeters. Models are also used to estimate changes in sea levels, particularly where no data are available.

Relative sea level rise (RSLR) is the combination of global mean sea level rise and local or regional changes in sea levels that occur due to land movements and other factors. Sea levels vary regionally as a result of vertical land movements (such as land subsidence or isostatic rebound), the ocean’s circulation, temperature and saltiness (called sterodynamic variability), and local gravitational changes due to ice melt from glaciers and ice sheets. Across the northern U.S. Gulf Coast, the rate of relative sea level rise is greater than the global average largely due to land subsidence, where the land is sinking due to physical and human activities. Conversely, in Alaska the land is rising in a process called isostatic rebound, which is the uplift of land that was once covered in ice during the last ice age and is now rebounding as the weight of that ice is removed. In those areas, relative sea levels are decreasing because the vertical lifting of the land has been greater than the rate of global mean sea level rise. While global mean sea level changes provide an important measure of a warming climate, it is changes in the RSLR that are most important for understanding impacts along the coasts.

Historical Trends in Sea Levels

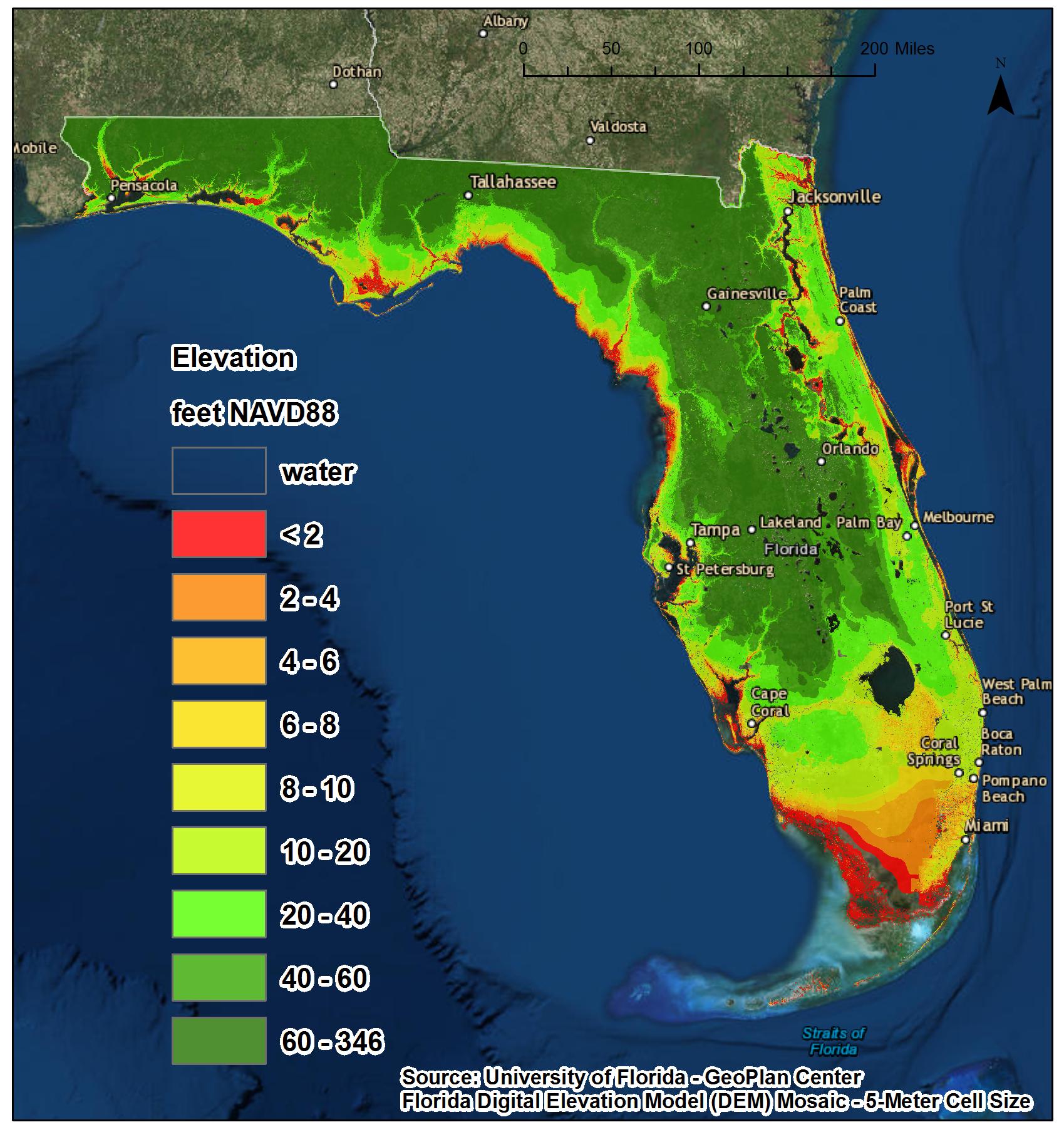

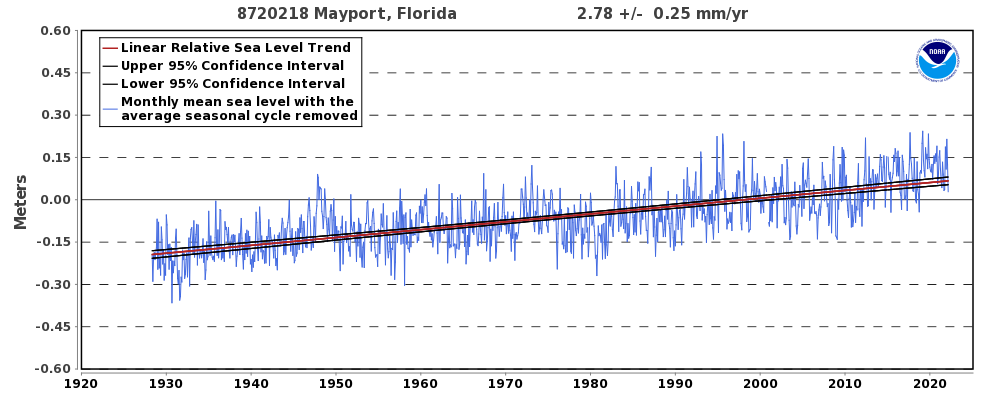

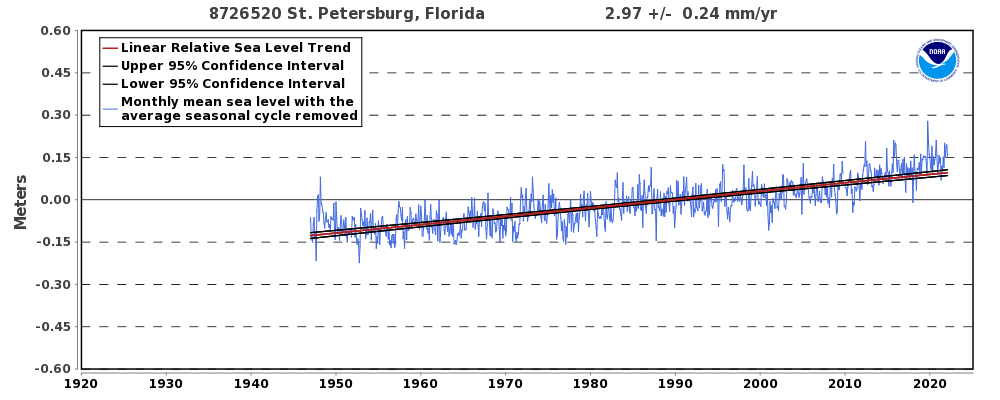

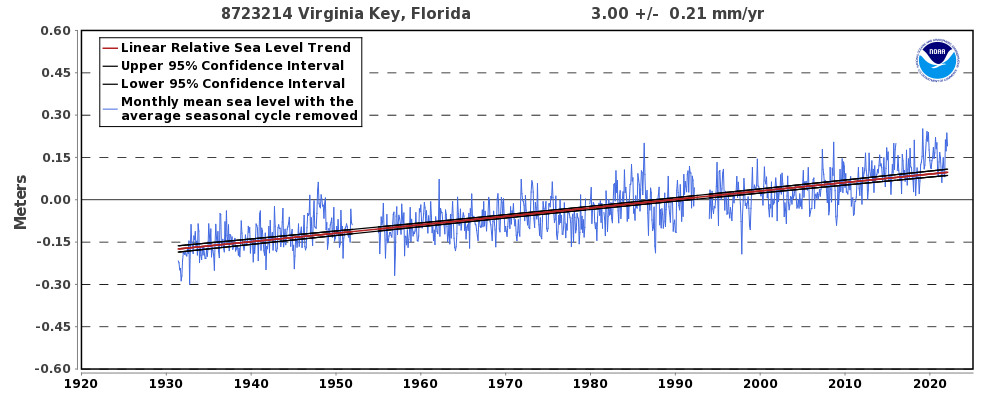

Satellite altimetry data indicate that the average rate of sea level rise in the Southeast U.S. region has been about 3.0 mm (0.12 inches) per year since the early 1990s, which is roughly equal to the global rate of sea level rise. Sea levels across Florida are as much as 8 inches higher than they were in 1950, and the rate of sea level rise is accelerating. For instance, sea levels around Virginia Key have risen by 8 inches since 1950, but they have been rising by 1 inch every 3 years over the past 10 years, based on tide gauge data. This acceleration in sea level rise is projected to continue. In the same area around Miami, sea levels increased 6 inches over the last 31 years, from 1985 to 2016, but they are expected to rise another 6 inches in half that time, over the next 15 years, according to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers high scenario projections. The graphs below show relative sea level trends from tide gauges around Florida’s coasts, from north to south. Each relative sea level trend is shown with the 95% confidence intervals and values are relative to the most recent mean sea level datum. The linear trend lines are also shown (in red). Note that the period of record for each tide gauge varies.

*Click on each graph to view a larger image.

Figure 2. Relative sea level trend for Apalachicola, Florida. Plotted values are relative to the most recent Mean Sea Level datum established by CO-OPS. Source: NOAA Tides and Currents.

Figure 3. Relative sea level trend for Mayport, Florida. Plotted values are relative to the most recent Mean Sea Level datum established by CO-OPS. Source: NOAA Tides and Currents.

Figure 4. Relative sea level trend for St. Petersburg, Florida. Plotted values are relative to the most recent Mean Sea Level datum established by CO-OPS. Source: NOAA Tides and Currents.

Figure 5. Relative sea level trend for Virginia Key, Florida. Plotted values are relative to the most recent Mean Sea Level datum established by CO-OPS. Source: NOAA Tides and Currents.

Future Sea Level Rise

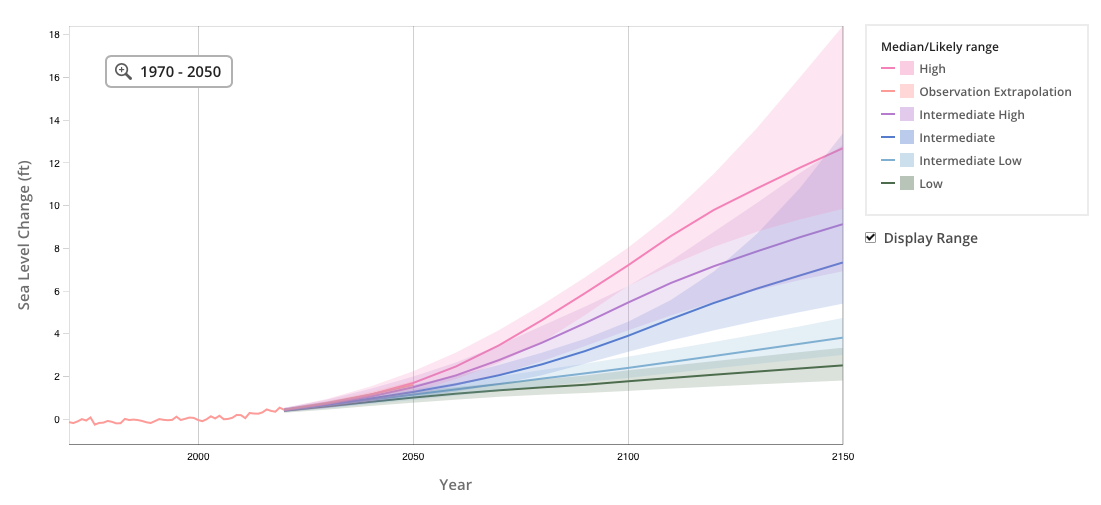

It is virtually certain that global mean sea levels will continue to rise throughout the 21st century and beyond. According to the latest science on sea level rise projections for the United States (Sweet et al. 2022), sea level rise over the next 30 years along the U.S. coastline is projected to be 10-12 inches (0.3 – 0.4 inches per year), on average, which will be as much as what has been measured over the past 100 years from 1920 to 2020. This is an indication of the acceleration in the rate of sea level rise that is expected to continue.

Confidence in relative sea level projections in the near term, out to the year 2050, has increased. Beyond 2050, sea level rise projections increasingly depend on the amount of greenhouse gas emissions, global temperature increases, and ice sheet melt in Antarctica and Greenland, making long-term sea level rise projections beyond 2050 less certain.

Projections in the relative sea level rise along the contiguous U.S. coastline range from 1.96 – 7.22 ft (0.6–2.2 m) by the year 2100 and 2.62 – 12.8 ft (0.8–3.9 m) by the year 2150, relative to sea levels in 2000. However, not all areas will experience the same amount, or rate, of sea level rise due to changes in local land and ocean heights.

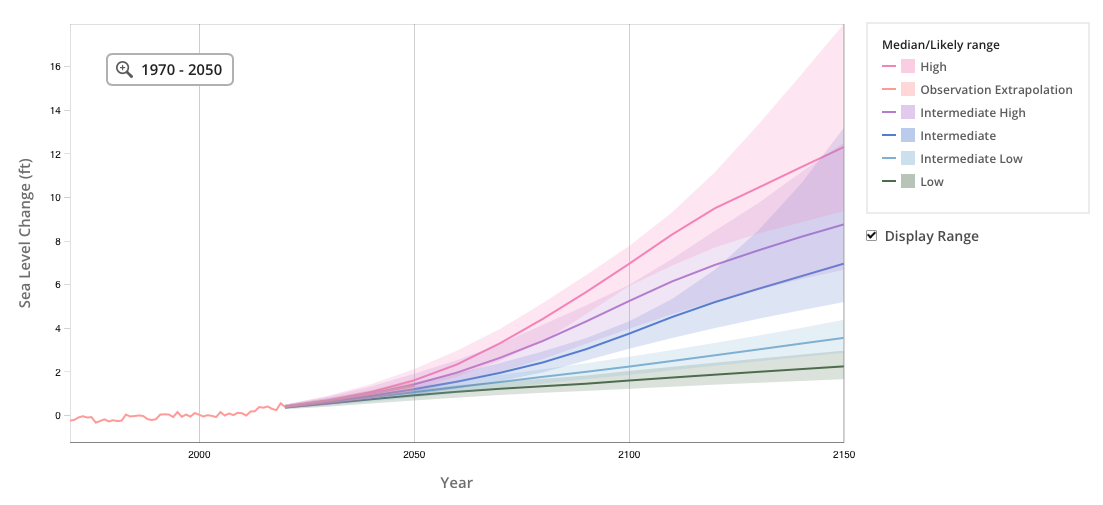

Shown below are regional sea level change time series graphs for the eastern Gulf Coast (Fig. 6) and Southeast Coast (Fig. 7). Projections are based on 5 sea level rise scenarios: low, intermediate-low, intermediate, intermediate-high, and high, out to the year 2150. Median values are provided for each scenario, along with likely ranges represented by shaded regions showing the 17th-83rd percentile ranges. For comparison to the model-based scenarios and as an additional line of evidence, extrapolations of available tide gauge observations are also provided. Rates and accelerations are estimated from tide gauge observations from 1970 to 2020 and then extrapolated to 2050. All values are relative to a baseline year of 2000. These graphs are from the Interagency Sea Level Rise Scenario Tool, based on data from Sweet et al. 2022.

*Click on each graph to view larger image.

Figure 6. Sea level rise projections out to 2150 under different sea level rise scenarios for the Eastern Gulf Coast. Source: Interagency Sea Level Rise Scenario Tool.

Figure 7. Sea level rise projections out to 2150 under different sea level rise scenarios for the Southeast US Coast. Source: Interagency Sea Level Rise Scenario Tool.

The Florida Flood Hub for Applied Research and Innovation, based at the University of South Florida College of Marine Science, estimated future increases in sea level along Florida’s coast. The table below provides the RSLR projections for coastal locations in Florida under two RSLR scenarios for the years 2040 and 2070, derived from data assembled for the 2022 Sea Level Rise Technical Report.

| 2040 | 2070 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intermediate-Low (ft) | Intermediate (ft) | Intermediate-Low (ft) | Intermediate (ft) | |

| Pensacola | 1.77 | 1.84 | 2.43 | 2.86 |

| Apalachicola | 1.68 | 1.75 | 3.24 | 2.77 |

| St. Petersburg | 1.61 | 1.68 | 2.27 | 2.70 |

| Naples | 1.52 | 1.59 | 2.18 | 2.61 |

| Key West | 0.88 | 0.95 | 1.54 | 1.97 |

| Miami Beach | 1.06 | 1.13 | 1.72 | 2.15 |

| Cape Canaveral | 1.93 | 2.00 | 2.59 | 3.02 |

| Mayport (Jacksonville) | 2.79 | 2.86 | 3.45 | 3.88 |

| Fernandina Beach | 3.57 | 3.64 | 4.23 | 4.66 |

Sea Level Rise Impacts

Sea levels are rising globally as a result of ocean warming and land-based ice melt; however, local coastal vulnerability and risk are driven by the total water level experienced at a given location based on the interaction of rising sea levels with astronomical tides, storm surges, and ocean waves. In Florida, sea level rise is already exacerbating saltwater intrusion and impacting groundwater supplies. Sea level rise is impacting gravity-flow drainage infrastructure, which is leading to more frequent and severe high tide (or “nuisance”) flooding. Higher sea levels can also lead to higher storm surge levels and greater coastal flooding during tropical cyclones.

Scientists are confident that sea levels will continue to rise over the coming decades. There is increasing confidence in near-term projections in sea level rise out to the year 2050, but greater uncertainty remains for longer term projections. Coastal communities across the state are already seeing the impacts from rising sea levels and are taking steps to address these impacts. In some low-lying coastal locations, sea level rise threatens to disrupt daily life, such as where streets are more often flooded with saltwater that can impact infrastructure and vehicles. As sea level rise continues and accelerates, more adaptation actions will be needed to minimize impacts and prepare communities for increased flood risks.

David F. Zierden, State Climatologist of Florida - (850) 644-3417 -

Emily Powell, Assistant State Climatologist of Florida - (850) 644-0719 -

The Florida Climate Center, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, 32301

April 29, 2014

Download report in PDF format  or read the report below

or read the report below

Introduction

As the State Climate office for Florida, we often get questions about living with high humidity. Many people suffer from respiratory illness or other health problems that are affected by humidity and they are trying to find a suitable climate to move to. The most common questions are:

Is Florida the most humid state in the nation?

Is There a Part of Florida that is Less Humid than Others?

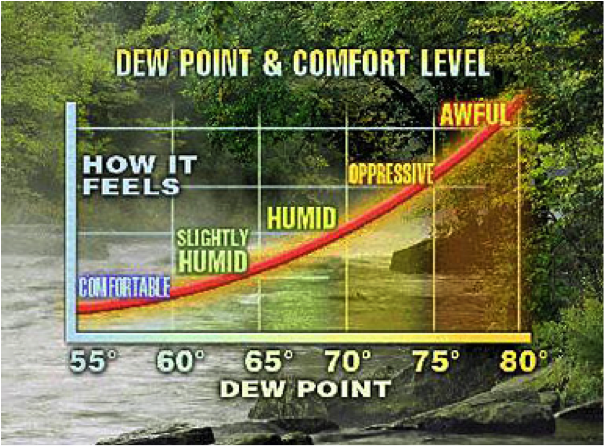

Before trying to answer these questions, it is best to have a brief discussion on how meteorologist measure and quantify humidity in the atmosphere.

Heat Index Climatology

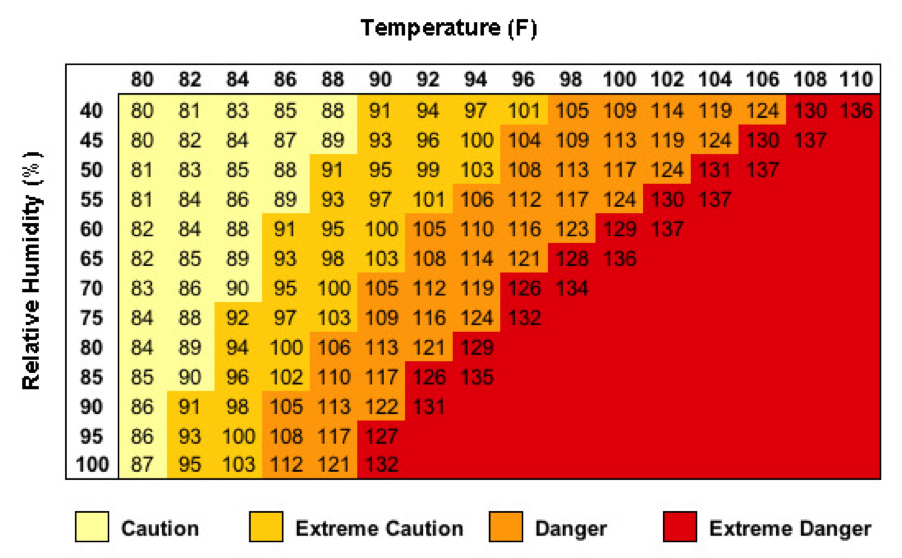

Heat index, also referred to as the ‘feels like’ temperature, is a measure of how hot it feels due to the relative humidity and actual air temperature. For example, using the chart above from the National Weather Service (NWS), if the temperature is 90ºF and the relative humidity is 65%, the heat index or how hot it feels is 103ºF. The NWS equation for heat index assumes shady and light wind conditions.

The heat index is used to determine when to issue local heat advisories and excessive heat warnings. Typically, a heat advisory is issued in Florida when the heat index during the next 24 hours is expected to reach or exceed 105ºF or 108ºF (depending on the location) for at least 2 hours. An excessive heat warning is issued when the heat index is expected to reach or exceed 113ºF in the next 24 hours.

View past heat index data for select stations in Florida:

- Pensacola

- Tallahassee

- Jacksonville

- Gainesville

- Tampa

- Orlando

- Daytona Beach

- Fort Myers

- Miami

- Key West

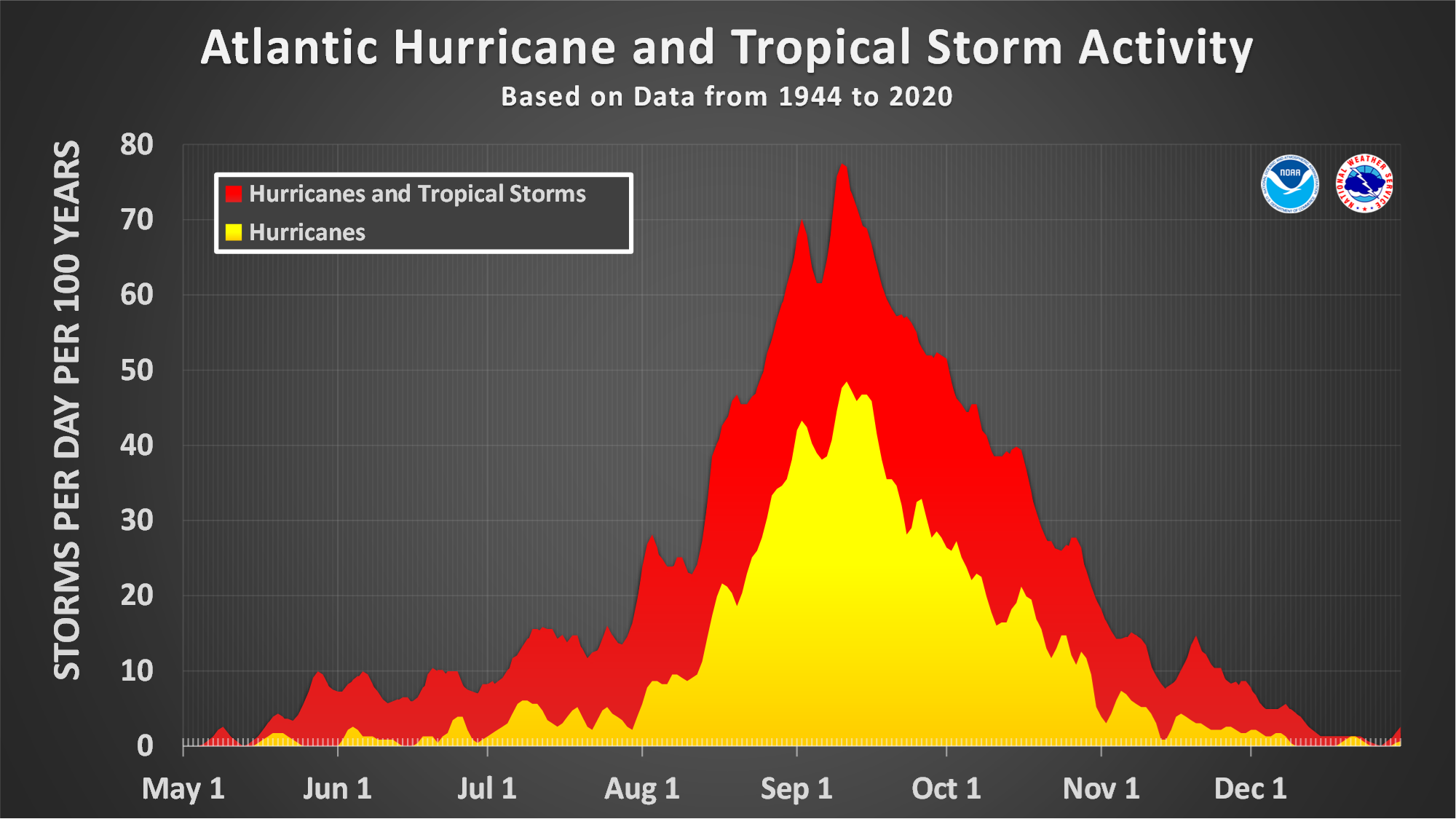

The threat of hurricanes is very real for Florida during the six-month long Atlantic hurricane season, which runs from June 1 until November 30. The peak of hurricane season occurs between mid-August and late October, when the waters in the equatorial Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico have warmed enough to help support the development of tropical waves.

A common misconception in Florida is that there are parts of the state that do not get hurricanes. Since 1850, all of Florida’s coastline has been impacted by at least one hurricane. With its long coastline and location, Florida frequently finds itself in the path of these intense storms. The southeast coastline is extremely susceptible to a land-falling hurricane, followed by the panhandle. Areas around Tampa, Jacksonville and the Big Bend do not have as high of a risk of a direct strike from a hurricane but are still susceptible to a landfall each year. Even if the hurricane makes landfall elsewhere in the state, the impacts can be felt hundreds of miles away.

Tropical Depression - A tropical cyclone in which the maximum 1-minute sustained surface wind is 33 knots (38 mph) or less.

Tropical Storm - A tropical cyclone in which the maximum 1-minute sustained surface wind ranges from 34 to 63 knots (39 to 73 mph).

Hurricane - A tropical cyclone in the Atlantic, Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, or eastern Pacific in which the maximum 1-minute sustained surface wind is 64 knots (74 mph) or greater.

Major Hurricane - A hurricane which reaches Category 3 (sustained winds greater than 110 mph) on the Saffir/Simpson Hurricane Scale.

Saffir-Simpson Scale

The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale, originally developed by Herb Saffir (wind engineer) and Bob Simpson (meteorologist), was used to categorize a hurricane based on its intensity at an indicated time. The scale classified the storm on a scale of one to five based on wind velocity, central pressure and height of storm surge.

Recent hurricanes brought to light some of the issues with trying to categorize hurricanes by so many different factors. Central pressure was not routinely measured from hurricanes prior to 1990. Hurricane size (the diameter of the entire storms), along with the extent of tropical storm force and hurricane force winds, local bathymetry, and forward motion were also not taken into account with the original Saffir-Simpson scale. To help reduce the confusion of the scale, the National Hurricane Center adapted a newer version of Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale in 2010, known as the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale, in which only the peak winds are now used to categorize a hurricane.

| SAFFIR-SIMPSON HURRICANE WIND SCALE | ||

| Very dangerous winds will produce some damage. | ||

| Extremely dangerous winds will cause extensive damage. | ||

| Devastating damage will occur. | ||

| Catastrophic damage will occur. | ||

| Catastrophic damage will occur. | ||

*Adapted from data from the National Hurricane Center’s Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale: http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/sshws_table.pdf.

Impacts

Winds are the most well-known impact from tropical storms and hurricanes. The highest winds occur just outside of the eye (or center) in a region known as the eye-wall. Hurricane force winds can easily damage or destroy mobile homes and other non-permanent structures, often moving them well away from their foundations. Roofs, trees and power lines are also frequently damaged by hurricane force winds. Because of Florida’s flat terrain, strong winds do not rapidly weaken after the storm makes landfall. Hurricane Charley in 2004 moved through the state at 25 mph (nearly twice the typical speed of a landfalling hurricane) and brought hurricane-force winds to Orlando, which was nearly 100 miles away from the point of landfall. The strongest hurricanes can have winds in excess of 155 mph.

Storm surge is the term used to describe the wall of water that is pushed toward the shoreline as a hurricane moves onshore. Storm surge combines with the local tide and the battering wind-driven waves to push a large volume of water onto the shore, often resulting in significant damage. In the strongest hurricanes, this storm surge can be as high as 25 feet above normal water levels. The combination of the rising water and pounding waves is often deadly. Approximately 90% of all deaths in hurricanes worldwide are caused by drowning in either the storm surges or flooding caused by intense rainfall. Those living in coastal and near-coastal communities should know if or in which evacuation zone they reside, as well as the elevation of their property.

Florida Evacuation Zone Information: https://www.floridadisaster.org/knowyourzone/

If local officials declare an evacuation for your area, move to the nearest evacuation destination outside of the declared zone. You may choose to stay with friends/relatives, at a hotel/motel or at an evacuation shelter.

Florida Evacuation Shelter Information: http://floridadisaster.org/shelters/

Flooding from tropical cyclones is not correlated with the intensity of the system but instead with the relative speed of the storm. Slow-moving tropical storms and hurricanes often produce large amounts of rain, which can lead to significant flooding at inland locations. Flooding impacts can occur hundreds of miles away from the center of a storm or from the remnants of a former tropical system.

Flooding from torrential rains can produce a lot of damage. Hurricane Easy in September 1950 dumped an estimated 38.70” of rain on Yankeetown, FL, in a 24-hour period. This amount cannot be counted as an official observation since it was estimated, so the official 24-hour state record rainfall amount (23.38”) came from the outer bands of Hurricane Jeanne in 1980.

Tornadoes associated with tropical systems typically form in the right front quadrant of the storm, relative to the direction of forward motion. If you were looking at the storm like it was a clock, this would be the area from about noon to three o’clock in the direction the storm is moving. While not normally as intense as tornadoes produced by non-tropical severe thunderstorms, these tornadoes often move very fast, at speeds over 50 mph. Another common area of tornadoes in a hurricane is in the far outer rain bands, which can be hundreds of miles away from the center of the storm.

Preparing for a Hurricane

There are a variety of lists to help you prepare for the upcoming hurricane season. The Florida Department of Emergency Management has come up with an interactive website to help you tailor these lists to your own household or business needs. Please take the time to go through the tool and make sure you’re prepared.

Create a Hurricane Plan for:

Your Family: https://www.floridadisaster.org/family-plan/

Your Business: https://www.floridadisaster.org/business/

| SOME NOTABLE HURRICANES IN FLORIDA'S HISTORY | |||

| Storm | Date | Category (at time of impact) | Landfall |

| Great Miami Hurricane | 1926 | 4 | South Miami |

| Lake Okeechobee Hurricane | 1928 | 4 | Jupiter |

| Labor Day Hurricane | 1935 | 5 | Craig Key |

| Unnamed | September 1947 | 4 | Pompano Beach |

| Unnamed | August 1949 | 4 | Palm Beach Shores |

| Hurricane Easy | September 1950 | 3 | Cedar Key |

| Donna | 1960 | 4 | Naples |

| Betsy | 1965 | 3 | Florida Keys |

| Eloise | 1975 | 3 | Bay County |

| Andrew | 1992 | 5 | Homestead |

| Opal | 1995 | 3 | Pensacola Beach |

| Charley | 2004 | 4 | Punta Gorda |

| Ivan | 2004 | 3 | Gulf Shores, AL |

| Jeanne | 2004 | 3 | Hutchinson Island |

| Dennis | 2005 | 3 | Santa Rosa Island |

| Wilma | 2005 | 3 | Cape Romano |

| Hermine | September 2016 | 1 | Alligator Point |

| Irma | September 2017 | 4 | Cudjoe Key |

| Michael | October 2018 | 5 | Mexico Beach, Tyndall Air Force Base |

| Sally | September 2020 | 2 | Gulf Shores, AL |

| Ian | September 2022 | 4 | Cayo Costa, FL |

| Nicole | November 2022 | 1 | near Vero Beach, FL |

| Idalia | August 2023 | 3 | Keaton Beach, FL |

| Helene | September 2024 | 4 | near Perry, FL |

| Milton | October 2024 | 3 | Siesta Key, FL |

CENTER FOR OCEAN-ATMOSPHERIC PREDICTION STUDIES

THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY

TALLAHASSEE, FL, 32306, USA

DIRECTOR: DR. JAMES J. O’BRIEN

REGIONAL EFFECTS OF ENSO ON U.S. HURRICANE LANDFALLS

By

CARISSA A. TARTAGLIONE

DEBORAH E. HANLEY

JAMES J. O’BRIEN

SHAWN R. SMITH

AUGUST 2002

TECHNICAL REPORT

2002-5

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FOREWORD

This is the MS thesis of Carissa Tartaglione. She now works at NOAA/NCDC. The research here is one of a series of papers on ENSO Impacts on the United States. We discovered these findings by serendipity.

The results are important. All regions of the US coast have an El Niño signal (less hurricanes). All regions have a La Niña signal (more hurricanes). On the Gulf Coast and Florida, La Niña and Neutral have the same signal. Along the East Coast of the U.S., the Neutral probability curve collapses on the El Niño curve. This means that during 75 percent of years, the East Coast has a reduced probability of hurricane landfall.

James J. O'Brien

Robert O. Lawton Distinguisded Professor

Meteorology and Oceanography

ABSTRACT

The effects of El Niño-Southern Oscillation on hurricane activity in the Atlantic Basin as a whole have been well established. It is known that El Niño suppresses hurricane activity while La Niña enhances it. Regional differences in the impact of El Niño/La Niña on hurricane landfalls have been observed in the Caribbean. The present study focuses on regional differences in the impact of ENSO on hurricane landfalls in the United States.

Hurricane landfall frequencies for Florida and the U.S. East Coast (Georgia to Maine) for El Niño, neutral, and La Niña years are presented. An increase compared to neutral years in Florida landfalling hurricanes for La Niña years is not observed; however, there are more hurricanes making landfall in Florida than along the East Coast during neutral years. Results for the Gulf Coast (Alabama through Texas) are nearly identical to those for Florida. La Niña appears to only increase hurricane landfall activity relative to neutral years from Georgia northward in the United States.

Most previous ENSO impact studies have shown differences in hurricane activity between El Niño , neutral, and La Niña phases. In this study, differences are only observed in one out of the three phases. Along the East Coast, the effects of the El Niño and neutral phases are essentially the same, such that the scenario becomes El Niño/neutral vs. La Niña. Along the coasts of the Gulf of Mexico and Florida, there is a similar scenario. In this case, the effects of the La Niña and neutral phases are nearly identical, creating a La Niña/neutral vs. El Niño scenario.

Examination of the origin points and tracks of landfalling hurricanes for both regions are examined and results show that storms making landfall along the East Coast are more likely to form in the central Atlantic while those that make landfall in Florida usually form further west, in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. Also, there are fewer storms forming in the neutral phase in the usual origin regions for East Coast landfalling hurricanes than there are in the cold phase. Possible explanations for the regional variation in the impact of ENSO on hurricane landfalls, such as the North Atlantic Oscillation and steering patterns, are suggested.

1

1. INTRODUCTION

Atlantic basin hurricane activity has doubled between 1995 and 2000, as compared to the preceding 24 years (Goldenberg et al. 2001). With the recent increase in Atlantic hurricane activity, growing coastal population, and the expected persistence of this trend, the need arises for a better understanding of the factors that influence hurricane activity. Numerous studies have investigated the role of various factors on hurricane activity in the North Atlantic; however, little focus has been placed on these influences regionally. Such information would be useful to many government agencies such as the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) for disaster relief planning.

The impact of El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) on hurricane activity has been well documented. Gray (1984) showed that El Niño conditions reduce hurricane activity in the North Atlantic basin. There are numerous characteristics of El Niño conditions that Gray attributed to the suppression of tropical cyclone activity. More discussion of these factors will be presented in Section 2.

Conversely, Gray (1984) and others have acknowledged that La Niña conditions, which are accompanied by weaker upper level westerlies and reduced vertical wind shear, tend to increase hurricane activity. Studies by Richards and O’Brien (1996) and Bove et al. (1998) agree with Gray’s observations, showing a decrease (increase) in hurricane landfall probabilities in the United States during El Niño (La Niña) events.

The study by Bove et al. (1998) revealed that the mean number of hurricanes to make landfall in the U.S. annually was 1.04 during El Niño years, 1.61 during neutral years, and 2.23 during La Niña years. It was also found that the probability of two or more hurricanes making landfall in the U.S. was 28% during El Niño, 48% during the neutral phase, and 66% during La Niña. The analysis by Bove et al. (1998) focused only on hurricane landfall probabilities for the United States as a whole and did not examine hurricane landfalls for the United States on a regional scale.

Tartaglione et al. (2002) have observed regional differences in the effects of ENSO on hurricane landfalls in the Caribbean. It was found that El Niño decreases hurricane landfall activity relative to the neutral phase for the entire Caribbean region. However, there were no differences observed in hurricane landfall probabilities between the El Niño and neutral phases in the East and West Caribbean.

It has been proven that large-scale circulation patterns produce different impacts regionally. A regional difference in the impact of ENSO on hurricane activity has been observed in the Caribbean. To date, there have been no studies that have determined the regional effects of ENSO phases on hurricane activity in the United States.

In this paper, hurricane landfall probabilities are calculated for Florida and the East Coast separately and the regional impact of ENSO in the U.S. is evaluated. Only landfalling hurricanes are considered for the following two reasons. First, the record of hurricane landfalls is more accurate than the record of all hurricanes. This is due to the fact that prior to the deployment of satellites in the 1960’s, open ocean hurricanes were more difficult to track and may not have been identified if they failed to hit land. Also, landfalling hurricanes are of more interest to the public because they have a direct impact on lives and property. For this study, only hurricane strength storms (those which make landfall with winds greater than or equal to 64 kts) are considered.

The number of hurricane landfalls in Florida and along the East Coast is determined for each year between 1900 and 1998 using the Atlantic Basin Best Track dataset provided by the National Hurricane Center and National Climatic Data Center (Neumann et al. 1993). Probabilities of hurricane landfalls for each region are evaluated for the warm (El Niño), neutral, and cold (La Niña) phases of ENSO. The origin points and tracks of Florida and East Coast landfalling hurricanes are also identified for each ENSO phase.

The analysis presented shows an increase in the probability of hurricane landfalls along the East Coast during La Niña years relative to neutral years. Surprisingly, there is virtually no difference in the number of Florida landfalling hurricanes during La Niña and neutral years is observed. Results found for the Gulf of Mexico were nearly identical to those for Florida. During La Niña, the average number of East Coast and Florida landfalling hurricanes is almost the same. Since the decrease in hurricane activity during El Niño is well-documented (Gray 1984) and noted in both study regions, this work will focus only on the La Niña and neutral phases from here on. The goals of this study are to examine regional differences in the impacts of ENSO on U.S. hurricane landfalls and to determine why there are fewer hurricane landfalls along the East Coast than in Florida during neutral years.

A detailed background including climate impacts, genesis mechanisms, and steering influences will be discussed in Section 2. The methodology will be presented in Section 3. Results are discussed in Section 4. Finally, a conclusion will be presented in Section 5.

2. BACKGROUND

a. Climate Impacts

The main factor Gray (1984) credited for the suppression of tropical cyclone development in the North Atlantic is an anomalous increase in the upper level westerly wind anomalies over the equatorial Atlantic and Caribbean Sea that is brought on by El Niño. More deep cumulus convection has been observed to be present during El Niño years (Gray 1984). This results in stronger upper level outflow, decreasing upper level anticyclonic flow, and further enhancing the westerlies. Since 200hPa winds must be easterly from 0º-15ºN and westerly from 20º-30ºN for conditions to be favorable for large numbers of tropical cyclones to form (Gray 1984), the conditions brought on by El Niño are unfavorable for hurricane development. The increase in upper level westerlies during El Niño results in increased vertical wind shear, which is known to suppress tropical cyclone formation and growth (Gray 1968). It is estimated that the upper tropospheric winds are anywhere from 2-7ms-1 more westerly during El Niño years than during non-El Niño years.

Gray (1984) also found that El Niño affected precipitation in the Caribbean very little. This suggests that tropical disturbances still exist during El Niño years; however, they are not developing into tropical cyclones. Thus, it is not a reduction in the amount of disturbances occurring that is brought on by El Niño, but unfavorable conditions for development which suppresses hurricane activity.

b. Tropical Cyclone Formation

The meteorological community has yet to come to an agreement on the physical mechanisms that lead to tropical cyclone development. This is largely due to the lack of upper-air observations available over the open ocean. Such a lack of observations hinders the development of a proper understanding of the factors that are responsible for tropical cyclone formation.

Although there is not a consensus on what exactly causes the development of tropical cyclones, several factors are widely accepted to be crucial to tropical cyclone genesis. There is a requirement for a pre-existing disturbance. Initial disturbances often arise from low level convergence coupled with upper tropospheric divergence and an increase in the mean tropospheric temperature (Gray 1968; Montgomery and Farrell 1993). The presence of a Tropical Upper Tropospheric Trough (TUTT) has also been identified as an influence on the development of tropical disturbances (Gray 1998; Montgomery and Farrell 1993). The TUTT acts to create upper level divergence and reduce vertical wind shear (Gray 1998).

Another key parameter established for tropical cyclone development is weak vertical wind shear (Gray 1968, 1998; Shapiro and Goldenberg 1998). The concentration of heat and condensation within a disturbance are hindered by strong vertical shear. Instead, the heat and condensation necessary for development are advected away from the disturbance (Gray, 1968). Thus, strong vertical wind shear does not allow for tropical cyclone formation.

The presence of low level relative vorticity (zr) has also been identified as a key factor in tropical cyclone genesis. In conjunction with a pre-existing disturbance, low level relative vorticity acts to enhance development. In fact, Weak vertical wind shear and large values of low level relative vorticity are listed by Gray (1998) as the two most influential factors in the development of tropical cyclones from existing disturbances.

Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) also play an important role in tropical cyclone formation. Palmen (1948) established that sea surface temperatures of 26.5ºC or higher are necessary for tropical cyclone genesis. This value has become widely accepted as a threshold. Shapiro and Goldenberg (1998) acknowledge the importance of decreased vertical wind shear, but indicate that hurricanes rarely develop if SSTs are below this value. Furthermore, Shapiro and Goldenberg (1998) stress that higher sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic are associated with above average tropical cyclone formation. The results of DeMaria et al. (2001) agree with the findings of Shapiro and Goldenberg (1998) that higher SST’s result in more tropical cyclones.

Various indices have been developed in an effort to predict tropical cyclone genesis. While many of these indices include similar factors, they all vary to some degree. Ward (1995) developed a parameter based on SST, vorticity, and tropospheric vertical shear. DeMaria et al. (2001) established a parameter using vertical shear, vertical instability, and mid-level moisture. They determined that early season tropical cyclone formation is limited most by vertical instability and mid-level moisture while late season formation is restricted more by vertical shear. DeMaria et al. (1998) also found these three parameters to be favorable for tropical cyclone development from the middle of July through the middle of October, which coincides with the peak of Atlantic hurricane activity.

Montgomery and Farrell (1993) noted that convective available potential energy present in moist convective cloud systems is an important source of energy for hurricanes. Upper level potential vorticity increases instability, thus they suggested that upper-level potential vorticity anomalies could initiate the formation of tropical cyclones. Montgomery and Farrell (1993) also identified tropical cyclone development as a result of the interaction between an easterly moving disturbance at lower levels and a westerly moving upper-level trough.

A more extensive index was established by Gray (1998) and is based on six factors which are seasonally averaged. These six factors are the Coriolis parameter, low level relative vorticity, the inverse of tropospheric vertical wind shear, ocean thermal energy (related to SST), the difference in the equivalent potential temperature between the surface and 500hPa (Dqe), and mid-tropospheric relative humidity. The "seasonal genesis parameter" is a product of what Gray refers to as the dynamic potential and the thermal potential. The dynamic potential is the product of the Coriolis parameter, the low level zr, and the inverse vertical wind shear. The thermal potential is the product of the ocean thermal energy, Dqe, and the relative humidity. Gray (1998) uses this seasonal genesis parameter to predict tropical cyclone formation.

It should also be noted that Shapiro and Goldenberg (1998) indicated the area from 10ºN-20ºN latitude to be the "main development region" in the Atlantic hurricane basin. This agrees with the results found by Gray (1968). However, Gray (1968) observed that the main regions of development in the North Atlantic exhibit a seasonal shift. The findings presented in this paper coincide with the results of Gray (1968) and Shapiro and Goldenberg (1998).

c. Tropical Cyclone Steering

Much like the case of tropical cyclone formation, little is understood about the conditions and mechanisms that control the movement of tropical cyclones. Once again, the lack of upper-air data presents a problem. Without adequate observations, it becomes difficult to identify what exactly controls the path that tropical cyclones take. Unfortunately, this lack of understanding manifests itself as a lack of agreement as to which factors steer tropical cyclones.

Many studies identified steering flow by a pressure averaged wind field. Most often, the middle tropospheric steering flows are used to predict the motion of tropical cyclones (Kasahara, 1959; Chan and Gray, 1982; Carr and Elsberry, 1990). It has also been noted by Kasahara (1959) that the position of the West Atlantic subtropical high plays a role in tropical cyclone movement.

Kasahara (1959) determined steering flow by solving the barotropic nondivergent vorticity equation. After establishing the steering flow, hurricane tracks were forecasted using an equation that included the interaction between the hurricane and the steering flow. Results showed that both the 500hPa and 700hPa flows predicted tropical cyclone paths rather well. Based on these results, Kasahara (1959) suggested that a vector mean of the 500hPa and 700hPa steering flow be used in forecasting the motion of tropical cyclones.

Carr and Elsberry (1990) found that tropical cyclones in the Northern Hemisphere that were moving westward had the tendency to move faster and to the left of the steering flow. They also noted that the motion of the tropical cyclone relative to the steering flow, referred to as propagation, was induced by b and depended on the strength of the outer winds of the tropical cyclone. In this study, it was suggested that a standardized steering flow be defined as the 850-300hPa pressure weighted wind over a 5º-7º latitude radius from the storm center.

Chan and Gray (1982) provided an extensive study of the relationship between tropical cyclone motion and environmental steering. In this study, tropical cyclones were stratified by direction and speed of motion, latitude, intensity change, and size. Steering flow was analyzed at various pressure levels and radii. The results showed that the 500-700hPa winds at a 5º-7º radius from the center of the storm were best correlated with tropical cyclone movement. It was observed that in the Northern Hemisphere, tropical cyclones move about 10º-20º to the left of the surrounding mid-tropospheric flow at a 5º-7º radius. Chan and Gray (1982) also found that tropical cyclones generally travel about 1 ms-1 faster than the surrounding flow. Although Chan and Gray (1982) found that the 500-700mb steering flow best determined tropical cyclone path, they note that the steering level that best indicates the movement of each tropical cyclone is influenced by vertical wind shear.

There are also factors that can complicate the prediction of tropical cyclone steering. Trough interactions may affect the track of a tropical cyclone (Hanley et al. 2001). The position of an upper-level trough can play a role in the direction that a tropical cyclone will move. Also, tropical cyclones are known to modify their own environment. These modifications can make it difficult to predict steering.

If the physical mechanisms that control hurricane formation and movement are known, they can be compared to the conditions associated with El Niño, neutral, and La Niña ENSO phases. A better understanding of tropical cyclone genesis and steering may provide an explanation of the regional variations in U.S. hurricane landfall activity.

3. METHODOLOGY

The Atlantic Basin Best Track dataset (Neumann et al. 1993) is used to determine hurricane landfalls. The Best Track dataset is composed of six-hourly observations (0Z, 6Z, 12Z, and 18Z) of storm center position, wind speed in knots, and pressure in millibars. A "landfalling" hurricane is defined as a storm that made at least one Florida, Gulf Coast, or East Coast landfall with winds greater than or equal to 64 kts. Once landfalling hurricanes are identified, each storm is then categorized as occurring during the onset summer of a warm, cold, or neutral ENSO year defined in Appendix A.

Hurricane landfall probabilities are determined using an inverse cumulative frequency distribution (IFCD). The IFCDs, also known as exceedence, show the probability that a certain number of hurricanes or more will make landfall during a particular ENSO phase. IFCDs are calculated for Florida, Gulf Coast, and East Coast landfalls. These regions are described in Appendix A.

Track plots are constructed using the storm center positions found in the Best Track data. These are separated by ENSO phase for the East Coast and Florida landfalling hurricanes. When "formation regions" are discussed, origin points are determined by the first position that is listed in the Best Track data for each storm. The first position marks the time that a named storm is identified as a tropical depression or stronger.

Monthly means of 1000, 850, 500, and 250hPa heights and winds as well as sea level pressure and SST fields are composited for cold and neutral hurricane seasons using the NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis Data (provided by the NOAA-CIRES Climate Diagnostics Center, Boulder, Colorado, from their website at http://www.cdc.noaa.gov/ ).

In addition to ENSO, the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) has been investigated for possible climate impacts on hurricanes. Tracks of major U.S. hurricanes were identified and correlated with phases of the NAO by Elsner et al. (2000). This study found that major hurricane activity at high and low latitudes are inversely related. Above normal activity at low latitudes was found to occur when activity at high latitudes were below normal and vice versa. This inverse relationship in major hurricane activity across latitudes was then related to phases of the NAO. Elsner et al. (2000) found that the Gulf Coast was more likely to see a major hurricane strike during a relaxed NAO while the East Coast was more likely to see a major hurricane strike during an excited NAO. In this work, the years of East Coast landfalls and Florida landfalls are also classified according to North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) phase (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. Years in which one or more hurricanes made landfall along the East Coast, classified by positive or negative NAO phase.

|

Positive NAO Phase |

Negative NAO Phase

1920

1901

1928

1933

1953

1936

1959

1947

1979

1952

1984

1960

1989

1985

1993

1996

Table 2. Years in which one or more hurricanes made landfall in Florida, classified by positive or negative NAO phase.

|

Positive NAO Phase |

Negative NAO Phase |

|

1919 |

1915 |

|

1921 |

1917 |

|

1926 |

1933 |

|

1928 |

1936 |

|

1935 |

1939 |

|

1945 |

1941 |

|

1946 |

1947 |

|

1948 |

1960 |

|

1950 |

1966 |

|

1953 |

1968 |

|

1979 |

1985 |

|

1992 |

1995 |

4. RESULTS

Between 1900 and 1998, a total of 60 hurricanes made landfall in Florida. Of those 60, 18 occurred during the 23 cold events, 6 made landfall during the 22 warm events and 36 hit during the 54 neutral events. During the same time period, only 46 hurricanes made landfall along the East Coast. There were 16 landfalls during the 23 cold years, 9 during the 22 warm years, and 21 landfalls during the 54 neutral years. The number of hurricane landfalls in both regions shows a clear inter-annual variability (Figs. 1 and 2). The largest number of hurricanes to hit either Florida or the East Coast in one year is three. This occurred in 1964 for Florida (Fig. 1) and in both 1954 and 1955 for the East Coast (Fig. 2). Since the results for the Gulf Coast (not shown) and Florida were nearly identical, only results for Florida and the East Coast will be discussed from this point on.

a. Landfall Probabilities

The ICFDs reveal a La Niña increase relative to neutral in hurricane landfalls along the East Coast, that is not present in Florida. During a cold event, the probability of two or more hurricanes hitting the East Coast is 18% vs. only 9% during a neutral event (Fig. 3). In Florida, the probability of two or more hurricanes making landfall is 22% during a cold event and 20% during a neutral event (Fig. 4). No warm phase year has produced more than one hurricane landfall in either Florida or along the East Coast. For both areas there is a decrease in hurricane landfalls in the warm phase, thus only the cold and neutral events will be discussed hereafter.

|

|

Figure 1. The number of hurricanes that made landfall in Florida each year between 1900 and 1998. El Niño years are indicated in red, neutral years are shown in green and La Niña years are indicated in blue.

|

|

Figure 2. The number of hurricanes that made landfall along the East Coast each year between 1900 and 1998. El Niño years are indicated in red, neutral years are shown in green and La Niña years are indicated in blue.

Initially, it would appear that there is no increase relative to neutral in the amount of hurricane landfalls in Florida during a cold event. However, the average number of hurricane landfalls per year for each ENSO phase reveals a notable difference in the neutral phase and not in the cold phase. For the East Coast there is an average of 0.7 hurricanes that make landfall per cold phase year (Fig. 5). In Florida, there is an average of 0.78 landfalling hurricanes per cold event (Fig. 6). During a neutral event, there are an average of 0.39 hurricane landfalls per year along the East Coast (Fig. 5) and 0.67 landfalling hurricanes per year in Florida (Fig. 6). There appears to be a significant decrease in hurricane landfalls during the neutral phase along the East Coast whereas compared to Florida. This would suggest that there is a dominant flow pattern during neutral years that tends to steer hurricanes toward Florida.

|

|

Figure 3. Inverse cumulative frequency distributions of East Coast landfalling hurricanes for warm, neutral, and cold phases, 1900-1998.

|

|

Figure 4. Inverse cumulative frequency distributions of Florida landfalling hurricanes for warm, neutral, and cold phases, 1900-1998.

|

|

Figure 5. Average number of hurricanes per year that made landfall on the East Coast from 1900-1998 during years classified by the JMA index as warm, neutral, or cold ENSO phases.

|

|

Figure 6. Average number of hurricanes per year that made landfall in Florida from 1900-1998 during years classified by the JMA index as warm, neutral, or cold ENSO phases.

b. Tracks of Landfalling Hurricanes

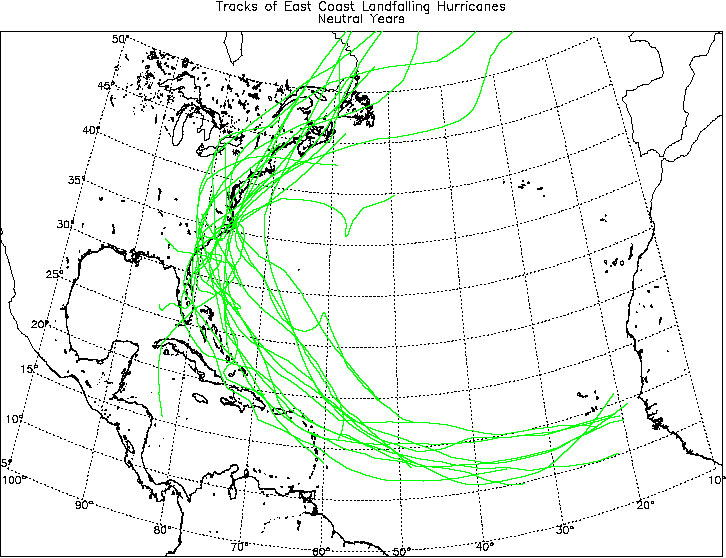

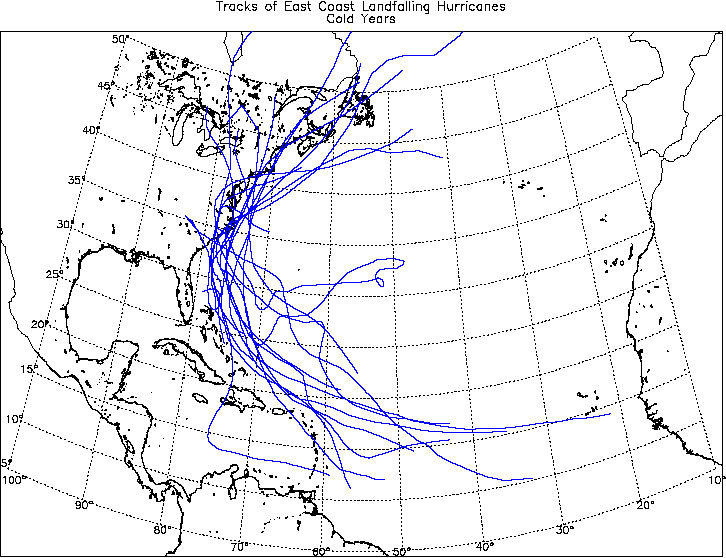

The tracks of hurricanes that make landfall along the East Coast during neutral years (Fig. 7) mainly originate in one region, off the Cape Verde Islands. These storms tend to recurve near the Leeward Islands and then head towards the East Coast. During the cold years, the East Coast landfalling hurricanes tend to form in the central Atlantic (Fig. 8). It is interesting to note that during the cold phase, no storm that makes landfall along the East Coast hits Florida first. Also, hurricanes that make landfall along the East Coast tend to hit further north during cold years than during neutral years (Figs. 7 and 8). Only five of the 46 hurricanes to make landfall along the East Coast between 1900 and 1998 made landfall in Georgia. Of these five, one hit during a warm year and the remaining four occurred during neutral years. No hurricane has ever made landfall in Georgia during a cold event. The tracks stay further to the east (Fig. 8), indicating the likely presence of an upper level trough that is blocking the storms from tracking any further west. This does not occur in the neutral phase (Fig. 7), thus more storms are able to push further west, hitting Florida as well as the East Coast.

|

|

Figure 7. Tracks of hurricanes that made landfall along the East Coast during neutral years

|

|

Figure 8. Tracks of hurricanes that made landfall along the East Coast during cold years.

c. Regions of Formation

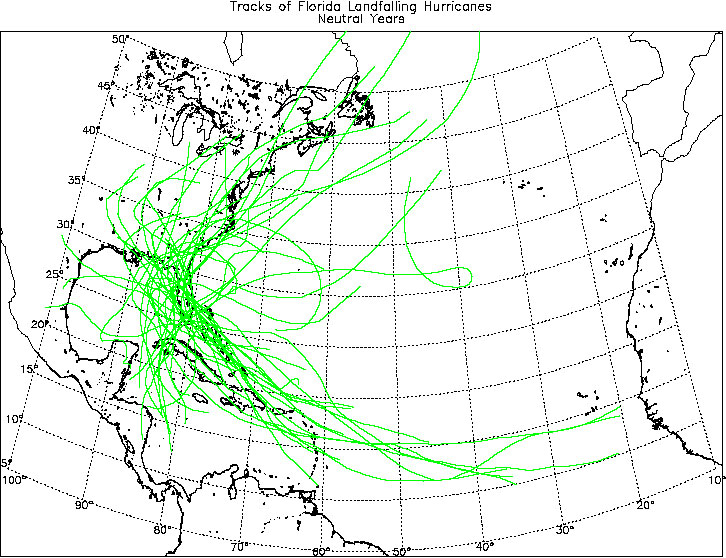

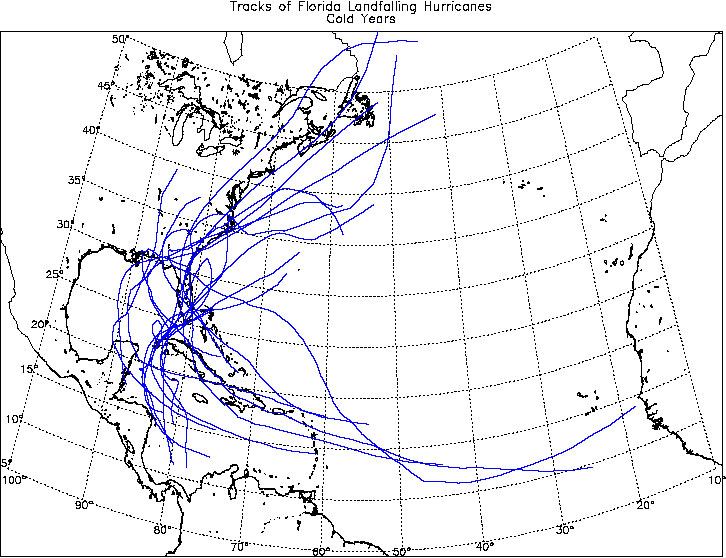

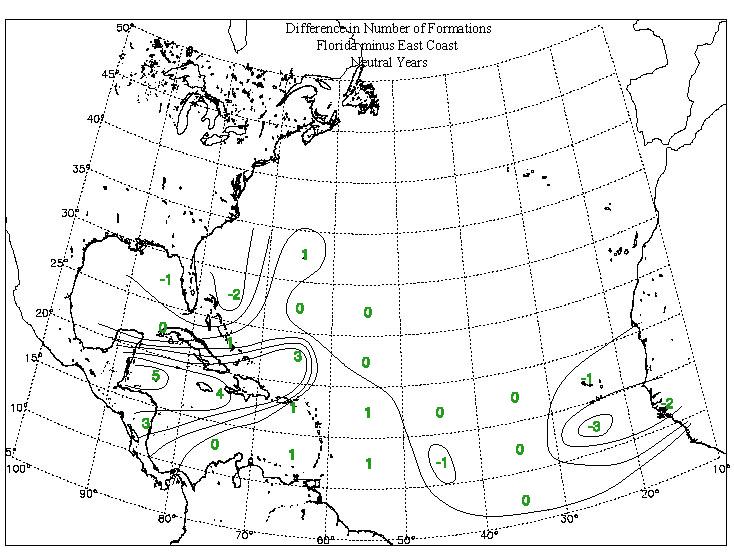

Florida landfalling hurricanes during both neutral and cold years originate in two different areas (Figs. 9 and 10). Most storms begin either in the central Atlantic or in the Caribbean. In the neutral phase, storms that form in the Caribbean and off Hispaniola are more likely to hit Florida than the East Coast (Fig. 11). While it is geographically logical that storms forming in the Caribbean will hit Florida, the storms forming to the northeast of Hispaniola are equally likely to hit either Florida or the East Coast. Storms forming off of the Cape Verde Islands during neutral years are more likely to hit the East Coast (Fig. 11).

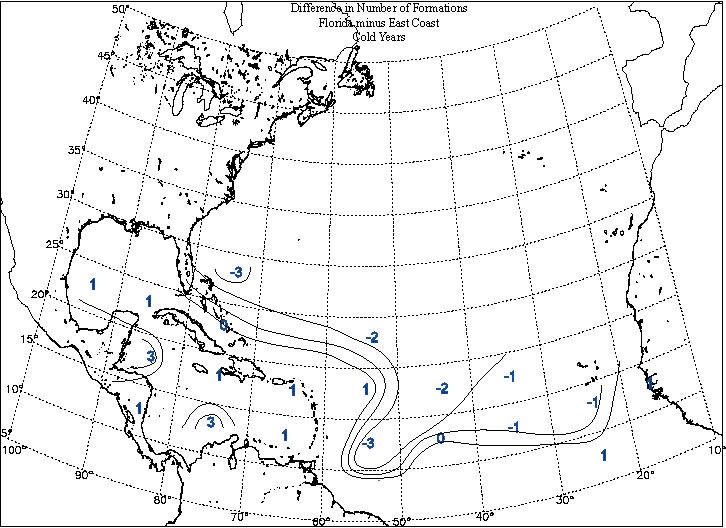

During the cold phase, the area of formation that is preferential for East Coast landfalling hurricanes extends further east to the central Atlantic (Fig. 12). This agrees with what is seen in the track plots (Figs. 7-10). The area of formation that is more likely for storms to make landfall in Florida during the cold phase is similar to that of the neutral phase (Figs. 11 and 12).

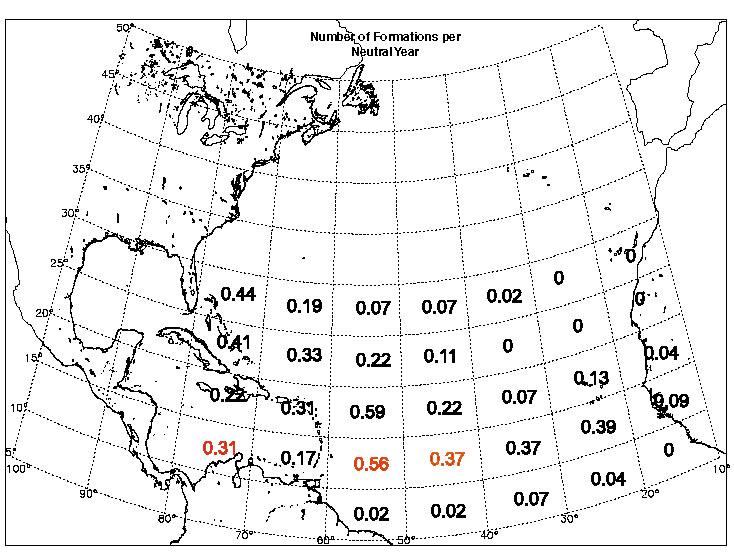

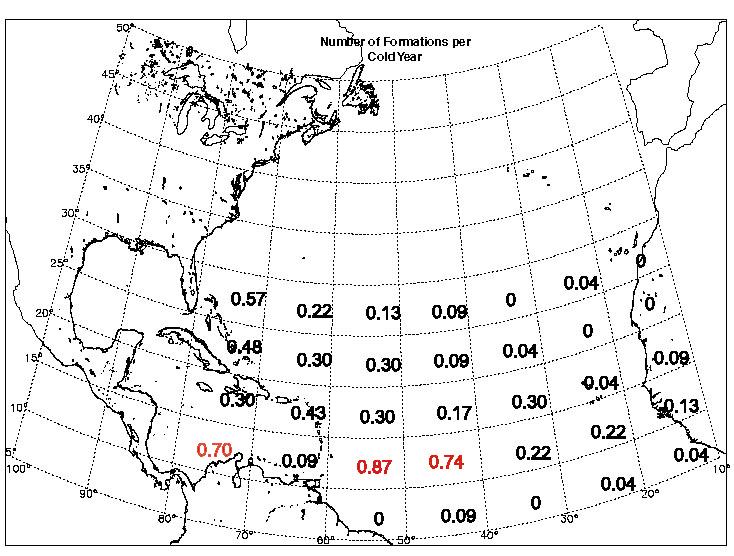

The main development region of Atlantic tropical cyclones is between 10ºN and 20ºN (Goldenberg et al. 2001). This is consistent with the formation regions identified in the present work. The main region of tropical cyclone formation during neutral years is between 10ºN-20ºN and 40ºW- 60ºW (Fig. 13). During cold phase years this region is narrower and located further South than during neutral years. The main region of tropical cyclone development for cold events is between 10ºN-15ºN and 40ºW-60ºW (Fig. 14). This is also the area of formation that is most favorable for East Coast landfalling hurricanes (Fig. 12). There are a greater number of tropical cyclone formations in this area during cold events than during neutral events. In the 5º by 10º box from 10ºN-15ºN and 50ºW-60ºW there are an average of 0.87 tropical cyclone formations per cold year (Fig. 14) and only 0.56 tropical cyclone formations per neutral year (Fig. 13). From 10ºN-15ºN and 40ºW-50ºW there is an average of 0.74 formations per cold year (Fig. 14), yet only 0.37 formations per neutral year (Fig. 13). The decrease in the number of all tropical cyclone formations during neutral years in the region most favorable for East Coast landfalling hurricanes contributes to the decrease in East Coast hurricane landfalls during neutral years.

|

|

Figure 9. Tracks of hurricanes that made landfall in Florida during neutral years.

|

|

Figure 10. Tracks of hurricanes that made landfall in Florida during cold years.

|

|

Fig. 11: The number of Florida landfalling hurricanes minus the number of East Coast landfalling hurricanes in each 5°x10° box for neutral years.

|

|

Figure 12. The number of Florida landfalling hurricanes minus the number of East Coast landfalling hurricanes in each 5°x10° box for cold years.

|

|

Figure 13. Number of tropical cyclone formations per neutral year.

|

|

Figure 14. Number of tropical cyclone formations per cold year.

d. Other Analyses

Some of the many factors, previously discussed in Section 2, that influence tropical cyclone formation and steering (i.e., SST, vertical wind shear) may explain the results found in this work. However, composites created from the NCEP Reanalysis monthly averaged fields (not shown) do not allow a detailed investigation of these factors to be performed. The monthly analyses are extremely smoothed, hence, the composites do not display a clear signal. Daily observations for each individual landfalling hurricane would most likely be able to detect differences between cold and neutral patterns better than monthly averages.

There does not appear to be any relationship between NAO phase and location of hurricane landfall. An equal number of positive and negative NAO phase years for both East Coast (Table 1) and Florida landfalls (Table 2) are observed.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The regional differences in hurricane landfall probabilities in the United States are identified with respect to the warm, neutral, and cold phases of ENSO. Emergency planners may benefit from the results of this study. With knowledge of the ENSO phase and its effects on a particular region, one can determine when the probability of a hurricane landfall is the highest. This can be useful to local, state, and federal emergency management agencies, particularly in coastal areas.

Relative to neutral events, the frequency of hurricane landfalls along the East Coast is found to increase (decrease) during ENSO cold (warm) events. This is consistent with previous studies linking ENSO and Atlantic hurricane activity. The hurricane season that occurs before a La Niña winter is the most likely to see a landfalling hurricane along the East Coast. In Florida, there is no difference observed in the frequency of hurricane landfalls between cold and neutral events. The lack of difference in cold and neutral hurricane landfalls in Florida as compared to the difference observed along the East Coast is due to a decrease in East Coast hurricane landfalls during neutral events rather than a decrease in Florida hurricane landfalls during cold events.

Tracks of landfalling hurricanes indicate that East Coast landfalling storms tend to form in the central Atlantic and curve northward just off the Leeward Islands while Florida landfalling storms are more likely to form further west. There are less storms forming in the central Atlantic, where East Coast landfalling hurricanes tend to form, during neutral years than during cold years. This may explain why there are fewer hurricanes making landfall along the East Coast than in Florida during neutral years.

The physical mechanism(s) that cause the decrease in hurricane landfalls along the East Coast during neutral years are not clear at the present time. Some factors that may contribute to this are lower SST’s and increased vertical shear during neutral years in the central Atlantic, resulting in the reduction of tropical cyclone formation where East Coast landfalling hurricanes are most likely to originate. It is possible that the subtropical high is more elongated during neutral years, blocking hurricanes from hitting the East Coast and causing them to track further south towards Florida. Also, stronger easterlies close to the equator during neutral years may be steering storms on a more zonal path, keeping them at lower latitudes and preventing them from reaching the East Coast.

Monthly averages of pressure, height, wind, and sea surface temperature fields were insufficient in revealing any particular pattern to explain the results obtained in this analysis. It is necessary to investigate these patterns on a smaller time scale. Six-hourly conditions of sea surface temperature, vertical shear, low level vorticity, and 500-700hPa winds in the week previous to each hurricane landfall would be more useful in determining the subtle differences in conditions during cold and neutral years. Also, a correlation between NAO phase and landfall region was not observed. Further investigation is needed in order to gain a better understanding of the mechanisms suppressing East Coast hurricane landfalls during neutral years.

APPENDIX A

The warm and cold phases of ENSO are often defined using an index of equatorial Pacific sea surface temperatures (SST). There has been much disagreement in the meteorological community as to which index best defines ENSO phases. Both the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) index and the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) have proven reliable for qualitative studies (Trenberth 1997; Hanley et al. 2002). For the present analysis, ENSO phases are classified according to the JMA index instead of the relatively noisy SOI index. The El Niño and La Niña periods identified by the JMA index compare well with many of the modern ENSO studies (Trenberth 1997).

The JMA defines a warm phase event when the five-month running average of sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies over the tropical Pacific (4°S-4°N, 150°W-90°W) is greater than 0.5ºC for at least six consecutive months including October, November, and December (JMA Atlas, 1991). A cold phase event is similarly defined when SST anomalies are less than -0.5ºC for at least six consecutive months including October, November, and December. All years that are not categorized as warm or cold are classified as neutral years.

An ENSO year is typically defined using the JMA index as the period from October in the year that the warm (or cold) phase develops until the following September. This definition is designed to capture the peak of an ENSO even in the boreal winter. Since the hurricane season runs from June through November, the typical ENSO year definition would split a hurricane season across two different ENSO years. Rather than classifying hurricane seasons using the standard ENSO definitions, hurricane seasons will be classified according to the onset year that the cold, warm, or neutral phase begins following the method of Bove et al. (1998). For example, the 1997 hurricane season is split between a neutral ENSO year from June through September and a warm ENSO year from October through November. According to Bove et al. (1998), the 1997 hurricane season is classified as a warm ENSO phase. ENSO classification for each hurricane season from 1900 to 1998 is displayed in Table 3. Using this method, 23 of the hurricane seasons in the 99-year period are classified as cold events, 22 are designated warm events, and 54 are categorized as neutral.

The regions focused upon in this work are the East Coast and Florida. The region defined as Florida includes the entire Florida coastline from Pensacola to Jacksonville. The East Coast is defined as the entire coastline from the Georgia/Florida border northward through Maine. Florida is treated individually from the East Coast. Some hurricanes make landfall in Florida, crossing the state and the re-entering the Atlantic where they regain strength and then hit the East Coast. These cases are treated separately as landfalls for both regions. The Gulf Coast (Alabama through Texas) was also considered in this study.

Table 3: ENSO Phases for Hurricane Seasons based on the JMA index. Row indicates decade, column indicates hurricane season. W denotes warm phase, N denotes neutral, and C denotes cold phase.

|

|

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

|

190 |

N |

N |

W |

C |

W |

W |

C |

N |

C |

C |

|

191 |

C |

W |

N |

W |

N |

N |

C |

N |

W |

N |

|

192 |

N |

N |

C |

N |

C |

W |

N |

N |

N |

W |

|

193 |

W |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

C |

N |

|

194 |

W |

N |

C |

N |

C |

N |

N |

N |

N |

C |

|

195 |

N |

W |

N |

N |

C |

C |

C |

W |

N |

N |

|

196 |

N |

N |

N |

W |

C |

W |

N |

C |

N |

W |

|

197 |

C |

C |

W |

C |

N |

C |

W |

N |

N |

N |

|

198 |

N |

N |

W |

N |

N |

N |

W |

W |

C |

N |

|

199 |

N |

W |

N |

N |

N |

N |

N |

W |

C |

|

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this research was provided by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administrations (NOAA) Office of Global Programs. Additional funding for this work was provided by NASA.

REFERENCES

Bove, M.C., Elsner, J.B., Landsea, C.W., Niu, X., and J.J. O’Brien, 1998: Effects of El Niño on U.S. Landfalling Hurricanes, Revisited. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 79, 2477-2482.

Carr, L.E. and R.L. Elsberry, 1990: Observational Evidence for Predictions of Tropical Cyclone Propagation Relative to Environmental Steering. J. Atmos. Sci., 47, 542-546.

Chan, J.C.L. and W.M. Gray, 1982: Tropical Cyclone Movement and Surrounding Flow Relationships. Mon. Wea. Rev., 110, 1354-1374.

DeMaria, M. J.A. Knaff, and B.H. Connell, 2001: A Tropical Cyclone Genesis Parameter for the Tropical Atlantic. Weather Forecast., 16, 219-233.

Elsner, J.B., K. Liu, and B. Kocher, 2000: Spatial Variations in U.S. Hurricane Activity: Statistics and a Physical Mechanism, J. Climate, 13, 2293-2305.

Goldenberg, S.B., C.W. Landsea, A.M. Mestas-Nuñez, and W.M. Gray, 2001: The Recent Increase in Atlantic Hurricane Activity: Causes and Implications. Science, 293, 474-479.

Gray, W.M., 1968: Global View of the Origin of Tropical Disturbances and Storms. Mon. Wea. Rev., 96, 669-697.

Gray, W.M., 1984: Atlantic seasonal hurricane frequency. Part I: El Niño and the 30 mb quasi-biennial oscillation influences. Mon. Wea. Rev., 112, 1649-1668.

Gray, W.M., 1998: The Formation of Tropical Cyclones. Meteor. Atmos. Phys. 67, 37-69.

Hanley, D., J. Molinari, and D. Keyser, 2001: A Composite Study of the Interactions between Tropical Cyclones and Upper Tropospheric Troughs. Mon. Wea. Rev., 129, 2570-2584.

Hanley, D.E., M.A. Bourassa, J.J. O’Brien, S.R. Smith, and E.R. Spade, 2002: A Quantitative Evaluation of ENSO Indices. J. Climate, accepted.

Japan Meteorological Agency, Marine Department, 1991: Climate Charts of Sea Surface Temperatures of the Western North Pacific and the Global Ocean. 51 pp.

Kasahara, A., 1959. A Comparison Between Geostrophic and Non-Geostrophic Numerical Forecasts of Hurricane Movement with the Barotropic Steering Model. J. Meteor., 16, 371-384.

Montgomery, M.T. and B.F. Farrell, 1993: Tropical Cyclone Formation. J. Atmos. Sci., 50, 285-310.

Neumann, C.J., B.R. Jarvinen, C.J. McAdie, and J.D. Elms, 1993: Tropical Cyclones of the North Atlantic Ocean. Prepared by the National Climatic Data Center, Asheville, N.C., in cooperation with the National Hurricane Center, Coral Gables, FL. 193 pp.

Richards, T.S., and J.J. O’Brien, 1996: The Effect of El Niño on U.S. landfalling hurricanes. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 77, 773-774.

Shapiro, L.J. and S.B. Goldenberg, 1998: Atlantic Sea Surface Temperature and Tropical Cyclone Formation. J. Climate, 11, 578-590.

Tartaglione, C.A., S.R. Smith, and J.J. O’Brien, 2002:ENSO Impact on Hurricane Landfall Probabilities for the Caribbean. J. Climate. (submitted)

Trenberth, K.E., 1997: The definition of El Niño. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 78, 2771-2777.

Ward, G.F.A., 1995: Prediction of Tropical Cyclone Formation in Terms of Sea-Surface Temperature, Vorticity, and Vertical Wind Shear. Aust. Meteor. Mag., 44, 61-70.

I. Introduction

It is now well-accepted that El Niño reduces hurricane activity in the Atlantic Basin. Gray (1984) uses physical processes that accompany El Niño to describe reduced hurricane activity. Gray (1984) also finds that of the 54 major hurricanes striking the United States coast during 1900-83, only four occurred during the 16 El Niño years in contrast to 50 making landfall during the 68 non-El Niño years. This is a rate of 0.25 major hurricanes per year during El Niño events and 0.74 during non-El Niño years, almost a three to one ratio. Richards and O'Brien (1996) showed that the probability of 2 or more hurricanes making landfall on the U.S. coast during El Niño is 21%, while the probability of 2 or more U.S. hurricanes during neutral conditions is 46%. However, the data and methodology used in Richards and O'Brien (1996) work are limited.

We reanalyze the frequency of hurricanes making landfall in the United States from 1900-1997 for the phases of the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Corrected U.S. hurricane data are used, and tropical storms are not considered in this study. The reanalysis shows that during an El Niño year, the probability of 2 or more hurricanes making landfall in the U.S. is 28%. The reanalysis further determines that the probability of 2 or more U.S. hurricanes during the other two phases is larger: 48% during neutral years and 66% during El Viejo. Also, we determine the range of these strike probabilities for El Niño and El Viejo. Strike probabilities of major U.S. hurricanes during each ENSO phase are also considered.

II. What is an El Niño?

El Niño (Warm Phase) involves an anomalous warming of the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. Here we base the definition of an El Niño event as developed by the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA Atlas, 1991) rather than the Southern Oscillation Index, which is relatively noisy.

The JMA Index defines El Niño events based on the sea surface temperature anomalies in the region 4° N to 4° S and 150° W to 90° W. An El Niño is identified when the five-month running average of SST anomalies is greater than 0.5° C for at least six consecutive months. The event must begin before September and include October, November, and December.

We also examine the opposite extreme of El Niño, which is known as El Viejo (Cold Phase or La Niña). The definition of El Viejo is chosen to be symmetric to that of the El Niño. Thus, an El Viejo occurs when the JMA SST index is 0.5°C below average for six consecutive months, starting before September and running through December. Years which do not meet the definition for either El Niño or El Viejo are considered neutral. The classification of each year is shown in Table 1.

Extremes in the ENSO cycle typically develop during summer, peak in late fall, and decay into the following spring. Therefore, for this analysis, we choose to define an ENSO year as the calendar year in which the El Niño develops. This definition is different than the JMA definition of an ENSO year, which runs from October of the year of development to the following September. Consequently, hurricane seasons are not broken up into 2 separate ENSO years. For example, under the JMA definition, the hurricane season of 1982 is considered neutral from June to September (considered JMA ENSO year 1981), then El Niño for October and November (JMA ENSO year 1982). With our change, the 1982 hurricane season falls entirely within ENSO year 1982.

III. Reasons For Reanalysis

There are three main limitations in the original work of Richards and O'Brien (1996). First, the JMA definition of an ENSO year was used, which breaks up a hurricane season into 2 separate events, as described above. Second, the original study only used 42 years of data, which is small for determining climatological changes. To increase the sample size, Richards and O'Brien (1996) used a resampling technique. This technique is known to be conservative with respect a measure of dispersion. Thus, the probabilities concerning El Niño U.S. hurricanes have likely been. Lastly, the data record of all U.S. hurricanes used in the original study included landfalls which never occurred. For example, the data used in Richards and O'Brien (1996) showed 2 U.S. hurricanes during JMA ENSO year 1957 (October 1957 - November 1958), when in actuality there were no U.S. hurricanes during this period.

IV. Histograms of Hurricane Landfall Occurrence

1. All U.S. Hurricanes

The sample size for examining North Atlantic hurricanes with respect to ENSO is small, with 22 El Niño years, 22 El Viejo years, and 54 neutral years. From these years, the number of U.S. hurricanes per ENSO phase is calculated. A tropical cyclone that makes at least one landfall somewhere in the U.S. as a hurricanes, or effects a portion of the U.S. coast with hurricane force winds, is considered a U.S. hurricane. Some U.S. hurricanes make multiple landfalls. Here we only consider the number of U.S. hurricanes, not the number of landfalls. Under this definition, the mean annual number of U.S. hurricanes during El Niño years is 1.04, 1.61 during neutral years, and 2.23 during El Viejo years. The number of U.S. hurricanes for each year is shown in Table 2.

The Poisson distribution is useful for describing rare, extreme events, such as the occurrance of hurricanes along the coastline. The Poisson distribution is characterized by the equality of the mean and variance. The ratio of the variance to the mean can be tested using a chi-squared (c2) distribution (Keim and Cruise 1998). Let the ratio R = s2 / mean, and N is the number of observations. R is tested against a critical R (Rc) obtained from c2N-1, a / (N - 1). With a = 0.10, Table 3 shows the test results stratified by ENSO events.

The ratios for neutral and cold events are close to unity, allowing us to assume a Poisson process (Elsner and Kara 1999, Elsner and Schmertmann 1993). Warm events are not Poisson permissible, so we adopt an empirical approach. Using these two methods, we find the probability of two or more hurricanes making U.S. landfall is 28% during El Niño, 48% during neutral years, and 66% during El Viejo (Figure 1).

The bootstrap technique (Draconis and Efron 1983) is used to determine confidence limits of U.S. hurricanes during warm and cold ENSO events. One thousand bootstrap records of U.S. hurricanes with respect to the ENSO phase are created with sample size of 22. The mean and empirical frequencies for each bootstrap sample are determined, and ranked in order to produce 5 and 95 percent confidence limits of the ENSO event. The same procedure is used for both the El Viejo and neutral years. In these cases the bootstrapped mean is used as the Poisson parameter.

Figure 2 shows the 5 and 95 percent confidence limits of U.S. hurricanes during El Niño. During El Niño, we are 90% confident that the probability of no hurricanes making U.S. landfall is somewhere between 17 and 24 percent. The probability of exactly one U.S. hurricane given an El Niño is between 45 and 58 percent, and the probability of two U.S. hurricanes during El Niño lies between 25 and 31 percent. Based on the historical data, there is no chance of more than 2 U.S. hurricanes during El Niño.

The probability of multiple U.S. hurricanes during El Viejo is significantly larger (Figure 3). The probability of not observing a U.S. hurricane during El Viejo ranges from 7 to 18 percent. The probability of exactly one El Viejo U.S. hurricane lies between 18 and 31 percent. The probability of exactly 2 U.S. hurricanes during El Viejo is about 26 percent, or once in every 4 cold phase years. For exactly 3 U.S. hurricanes, the probabilities vary between 15 and 22 percent, and for exactly 4 U.S. hurricanes the range is from 7 to 15 percent.

As seen in Figures 2 and 3, the probability range of exactly one U.S. hurricane is actually higher during warm phase than during cold phase. The probability spread of one U.S. hurricane is the same for both extreme events, however, with both warm and cold phases exhibiting a 90% confidence interval of 13 percent: warm phase from 45 to 58 percent, cold phase from 18 to 31 percent. For exactly 2 U.S. hurricanes, the probabilities are about the same between warm and cold events. The range of 90% confidence is quite narrow during cold phase for exactly 2 U.S. hurricanes, giving us a high degree of confidence that the probability is close to 26 percent. For warm phase, the range of probabilities is larger.

Taking the inverse cumulative frequency distributions of these confidence intervals and comparing the two phases shows the dramatic differences ENSO makes in U.S. hurricane activity (Figure 4). For example, the probability range of 2 or more U.S. hurricanes during El Niño (with 90% confidence) is 25 to 31 percent. For El Viejo, the probability for 2 or more U.S. hurricanes is much greater, ranging from 51 to 76 percent.

2. Major U.S. Hurricanes

Major U.S. hurricanes (hurricanes making U.S. landfall with sustained winds of 96 knots or more) are of even more interest due to the larger amount of damage they can produce (Pielke and Landsea 1998). The impacts of ENSO on major U.S. hurricanes are similar to those for all U.S. hurricanes. There are 63 major U.S. hurricanes in the past 98 years, 5 during El Niño, 37 during neutral conditions, and 22 during El Viejo. The mean annual number of major U.S. hurricanes is 0.23 for El Niño, 0.68 for neutral conditions, and 0.95 for El Viejo conditions. The number of major U.S. hurricanes per year is shown in Table 4 (Neumann et al. 1993).

Here only empirical data is used to determine return frequencies of major U.S. hurricanes. Figure 5 shows that during an El Niño, the probability of at least one major U.S. hurricane is about 23 percent. The probabilities for at least one major U.S. hurricane during the other two phases are much higher: 58% for neutral conditions and 63% during a cold event. The United States is much more likely to see a major hurricane during neutral or cold events than during El Niño.

During the past 98 years, no El Niño event has ever been associated with more than one major U.S. hurricane. In contrast, the data shows there is a 27% chance for 2 or more major U.S. hurricanes during cold phase and a 8% chance during neutral conditions. It is also possible to see three major hurricanes during these phases of the ENSO cycle: 9% for cold phase, and 2% for neutral. No year has seen 4 or more major U.S. hurricanes.

V. Conclusions

Here we quantitatively relate the impacts of warm (and cold) sea surface temperature anomalies in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean to the number of hurricanes making landfall in the United States. Whether or not an El Niño event is identified during the early summer, as it was in 1997, the potential for a major outbreak of U.S. hurricanes in an El Niño year is significantly decreased. The chance of a major U.S. hurricane is reduced as well.

Acknowledgments

The Center for Ocean-Atmospheric Prediction Studies (COAPS) receives its base support from the Secretary of the Navy Grant to James J. O'Brien. Additional support for this work was received from the Office of Global Programs, NOAA. The second author received support from NSF and the Risk Prediction Initiative (RPI).

References

Draconis, P. and B. Efron, 1983. Computer-intensive methods in statistics. Sci. Amer., 248, 116-130.

Elsner, J. B. and Schmertmann, 1993: Improving extended-range seasonal predictions of intense Atlantic hurricane activity. Wea. Forecasting, 8, 345-351.

Gray, W. M., 1984. Atlantic seasonal hurricane frequency. Part I: El Niño and 30 mb quasi-biennial oscillation influences. Mon. Weath. Rev., 112, 1649-1668.

Elsner, J. B., and A. B. Kara, 1999: Hurricanes of the North Atlantic: Climate and Society, Oxford, In press.

Japan Meteorological Agency, Marine Department, 1991. Climate Charts of Sea Surface Temperatures of the Western North Pacific and the Global Ocean. 51 pp.

Keim, B. D., and J. F. Cruise, 1998: A technique to measure trends in the frequency of discrete random events. J. Climate, 11, 848-855.

Neumann, C.J., B. R. Jarvinen, C. J. McAdie, and J.D. Elms, 1993: Tropical Cyclones of the North Atlantic Ocean. Prepared by the National Climatic Data Center, Asheville, NC, in cooperation with the National Hurricane Center, Coral Gables, FL. 193 pp.

Pielke, Jr., R. A., and Landsea, C. W., 1998: Normalized U. S. hurricane damage, 1925-1995. In press, Wea. Forecasting.

Richards, T. S., and J. J. O'Brien, 1996. The effect of El Niño on U.S. landfalling hurricanes. Bulletin of the Amer. Met. Soc., 77, 773-774.

List of Tables

Table 1. List of ENSO years, based on the JMA-SST Index. The column indicates the decade, and the row indicates year. 'W' indicates a warm phase, 'C' indicates a cold phase, and 'N' indicates neutral conditions.

Table 2. List of U.S. hurricanes per year. The column indicates the decade, the row indicates the year.

Table 3. Results of Poisson tests on annual means and variances of the number of U.S. landfalling hurricanes by ENSO events.

Table 4. List of major U.S. hurricanes per year. The column indicates the decade, the row indicates the year.

List of Figures

Figure 1. Inverse cumulative frequency distributions of US landfalling hurricanes, 1900-1997.

Figure 2. Probability distributions of U.S. hurricanes at the 5 and 95 percent confidence levels for the ENSO warm phase.

Figure 3. Probability distributions of U.S. hurricanes at the 5 and 95 percent confidence levels for the ENSO cold phase.

Figure 4. Inverse cumulative frequency distributions of U.S. hurricanes at 5 and 95 percent confidence levels for warm and cold phases of ENSO.

Figure 5. Inverse cumulative frequency distributions of major U.S. hurricanes, 1900-1997.

Table 3

Table 4

|

Figure 1 |

|

Figure 2 |

|

Figure 3 |

|

Figure 4 |

|

Figure 5 |

Copyright 1998, Bove et al. All Rights Reserved