The Florida Climate Center serves as the primary resource for climate data, information, and services in the state of Florida.

What's new in our world?

The Florida Climate Center achieves its mission by providing climate monitoring, research, and expertise to be applied by the people, institutions, and businesses of Florida and the surrounding region.

We provide direct service by fulfilling requests for climate and weather data and information in a variety of formats.

We perform research that advances the understanding of the climate variability and changes of Florida and the surrounding region.

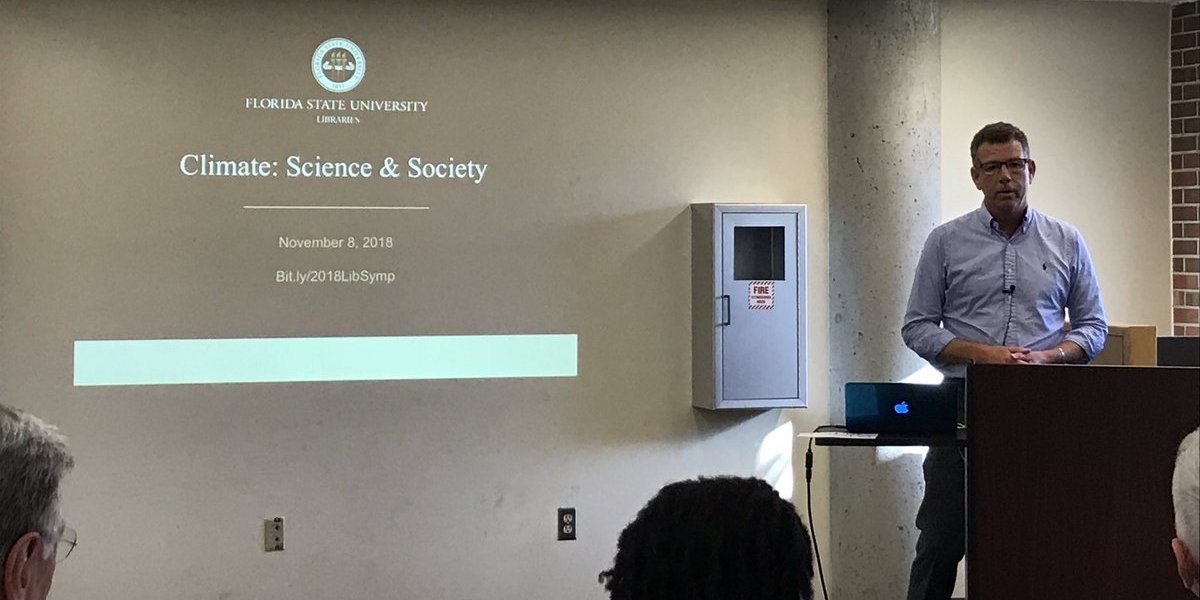

We provide outreach in presentations and at events aimed at a variety of groups, interests, and ages.

CONTACT: David F. Zierden, State Climatologist of Florida

(850) 644-3417;

October 30, 2013

Download report in PDF format  or read the report below

or read the report below

CONTACT: David F. Zierden, State Climatologist of Florida

(850) 644-3417;

March 14, 2014

Download report in PDF format  or read the report below

or read the report below

Outlook Summary

- Early spring should bring variable weather patterns, as we have experienced this winter. There is no tendency towards wetter and cooler or warmer and drier with neutral conditions in the Pacific.

- Summer may bring normal to above normal rainfall, but seasonal predictions for the summer are difficult and have low confidence.

- There is a greater than 50% chance the Pacific Ocean transitions to El Niño during the summer.

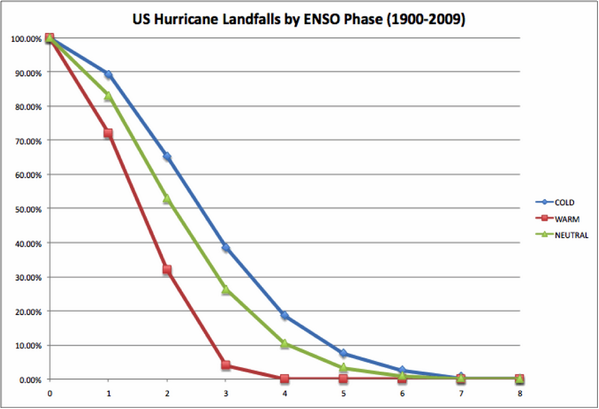

- A developing El Niño would mean a less active Atlantic hurricane season.

- A very wet summer followed by near normal winter rainfall and recharge has surface water, groundwater, and soil moisture in good shape going into spring and summer.

- Florida wildfire season has been relatively quite thus far. As long as summer rains begin on time, an active season is not anticipated.

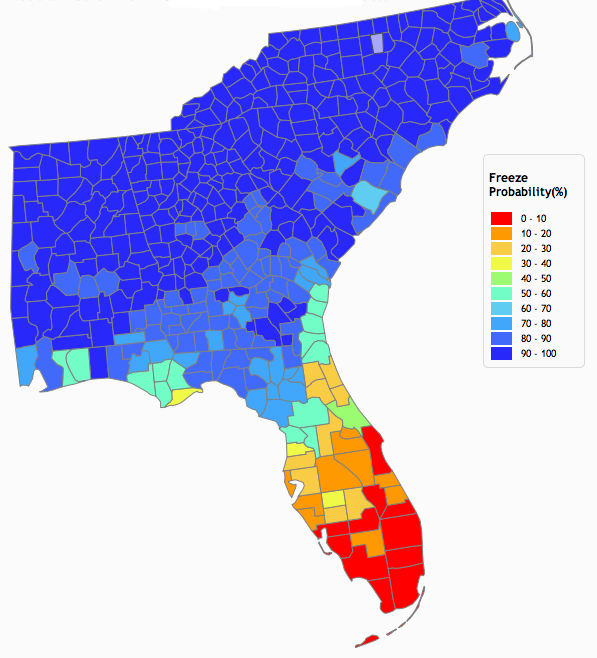

From AgroClimate.

Date updated: November 13, 2009

El Niño reaches moderate strength and continues to build in the Pacific Ocean.

|

|

|

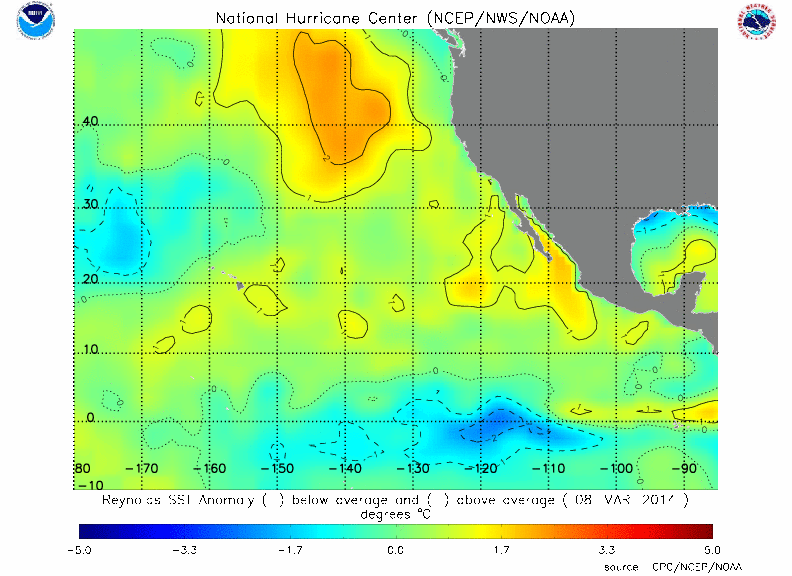

Current East Pacific SST Analysis |

Current East Pacific SST Anomaly Analysis |

| Click on each image for a full-size version. | |

Ocean temperatures in the past few months have continued to warm in the eastern and central tropical Pacific Ocean and are now over 1.0 degree C warmer than normal over a large area. Sea surface temperatures in this region of 0.5 degree C warmer than normal are the commonly used threshold to designate El Niño conditions. El Niño refers to a periodic (every 2-7 years) warming of the tropical Pacific Ocean along the equator from the coast of South America to the central Pacific. Once surface temperatures warm to over 1.0 degrees C the El Niño is considered moderate in strength (the three classifications are weak, moderate, and strong). This warming began in May and has continued through the summer and fall months. The development of this El Niño follows the typical life cycle of building in the summer and fall months before reaching peak strength in mid winter.

Weakened trade winds over the central Pacific and abundant warm water beneath the surface indicate that surface temperatures will continue to warm in the next 1 to 3 months. Modeling centers around the world that predict El Niño/La Niña agree that waters will continue to warm and result in at least a moderate El Niño during the winter and spring months. There is a small chance that the El Niño will reach the strong category. There is no chance of La Niña returning in the near future and very little chance of neutral conditions.

The development of El Niño could have dramatic impacts on the climate of the Southeast for the remainder of 2009. First, El Niño hinders hurricane development in the Atlantic basin and is largely responsible for the relatively quiet season thus far. El Niño has its strongest impacts on the Southeast in the colder months, bringing wet, stormy, and cool winter and spring seasons to the Southeast. For more detailed information on climate impacts in the Southeast, see the latest climate outlook.

The SECC tracks the temperatures of the Pacific Ocean using the JMA index. For more information and current JMA values, see the following link:

Other El Niño/La Niña Forecasts

Below are links to El Niño/La Niña forecasts from other centers in the U.S. and worldwide. Caution: the SECC may not agree with their forecasts and/or classification criteria.

From AgroClimate.

Date updated: July 6, 2009

The Pacific Ocean is currently transitioning into the El Niño phase.

|

|

| Current East Pacific SST Analysis | Current East Pacific SST Anomaly Analysis |

| Click on image for a full-size version. | |

Ocean temperatures in the past month have warmed rapidly in the eastern and central tropical Pacific Ocean and are now above the 0.5 C threshold that commonly designates El Niño conditions. This warming completes the transition from a weak La Niña in March of 2009 through several months of neutral conditions in April, May, and June, to impending El Niño for the remainder of 2009. El Niño refers to a periodic (every 2-7 years) of the tropical Pacific Ocean along the equator from the coast of South America to the central Pacific. Weakened trade winds over the central Pacific and abundant warm water beneath the surface indicate that surface temperatures will continue to warm in the next few months. Modeling centers around the world that predict El Niño/La Niña agree that waters will continue to warm and result in a weak to moderate El Niño over the next 3-6 months. NOAA's Climate Prediction Center issued an "El Niño watch" in early June, meaning that the development of El Niño conditions are likely in the next 1-3 months.

If El Niño fails to develop as forecast, then neutral conditions will be the other possibility. There is virtually no chance for a return to La Niña in 2009.

The development of El Niño could have dramatic impacts on the climate of the Southeast for the remainder of 2009. First, El Niño hinders hurricane development in the Atlantic basin and leads to less active seasons. El Niño events that develop this early in the summer can lead to drier than normal conditions across Alabama and Georgia in the late summer and early fall. El Niño has its strongest impacts on the Southeast in the colder months, bringing wet, stormy, and cool winter and spring seasons to the Southeast. For more detailed information on climate impacts in the Southeast, see the latest climate outlook.

The SECC tracks the temperatures of the Pacific Ocean using the JMA index. For more information and current JMA values, see the following link:

Other El Niño/La Niña Forecasts

Below are links to El Niño/La Niña forecasts from other centers in the U.S. and worldwide. Caution: the SECC may not agree with their forecasts and/or classification criteria.

From AgroClimate.

Date updated: July 7, 2009

Big Changes in the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is transitioning into the El Niño Phase. Ocean temperatures in the past month have warmed rapidly in the eastern and central tropical Pacific Ocean and are now above the 0.5 C threshold that commonly designates El Niño conditions. This warming completes the transition from a weak La Niña as late as March 2009 through several months of neutral conditions in April, May, and June, to impending El Niño for the remainder of 2009. El Niño refers to a periodic (every 2-7 years) warming of the tropical Pacific Ocean along the equator from the coast of South America to the central Pacific.

Sea surface temperature departures from normal (degrees C) over The Pacific Ocean as of July 1.

Weakened trade winds over the central Pacific and abundant warm water beneath the surface indicate that surface temperatures will continue to warm in the next few months. Modeling centers around the world that predict El Niño/La Niña are in good agreement that waters will continue to warm and result in a weak to moderate El Niño over the next 3-6 months. NOAA's Climate Prediction Center issued an "El Niño watch" earlier in June, meaning that the development of El Niño is likely in the next 1-3 months. If El Niño fails to develop as forecasted, then neutral conditions will be the other possibility. There is virtually no chance for a return to La Niña in 2009.

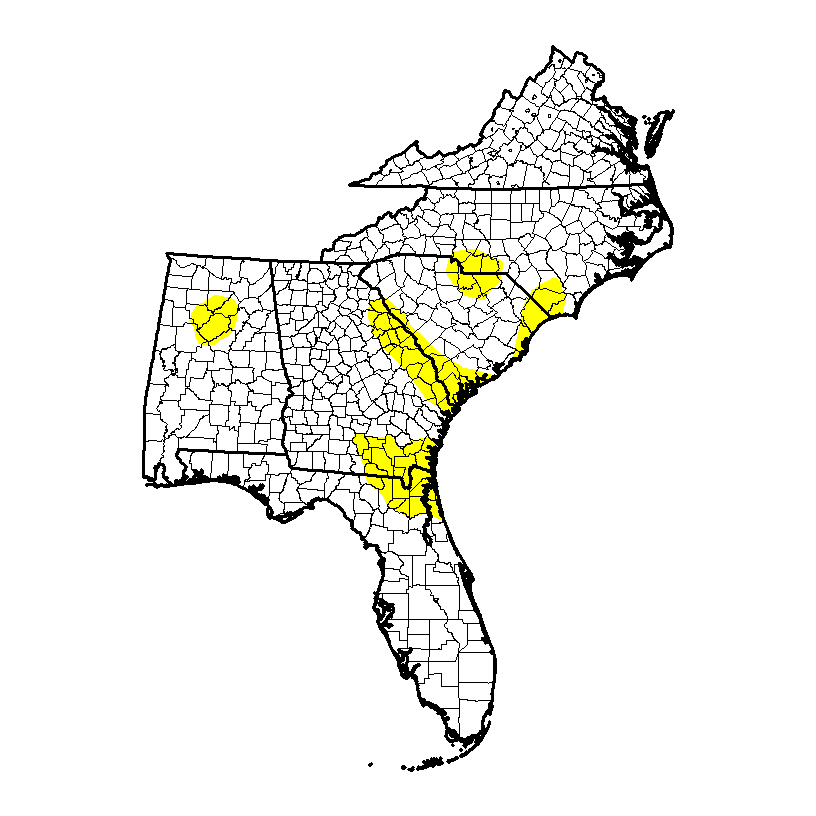

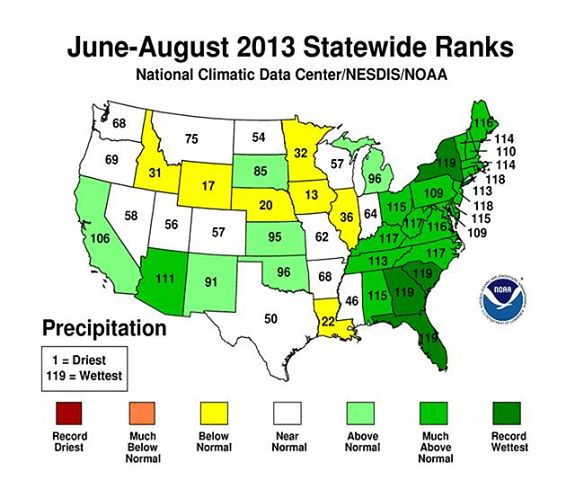

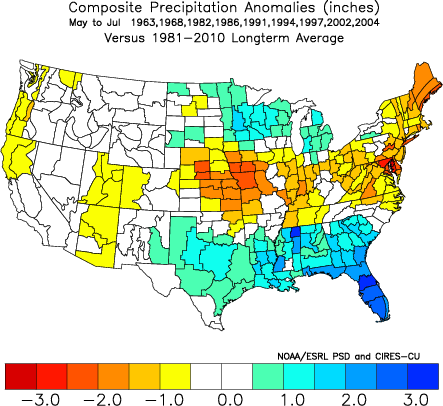

What does El Niño mean for the rest of the summer? When an El Niño develops this early in the summer (they usually form in the fall and reach peak strength in the winter months), it has the potential to lead to drier than normal weather patterns across the Southeast in the second half of summer and in early fall. This tendency towards drier weather is strongest over Alabama, north Georgia, and the Carolinas where rainfall averages 10% to 20% less than normal in July and August during El Niño.

Average changes in precipitation (percent change from normal) for August during El Niño episodes

Over much of inland Alabama and Georgia, this is the time when evapotranspiration normally exceeds rainfall, meaning soil moisture, surface water, and groundwater levels usually decline until the following winter. Summer does bring frequent afternoon thundershowers, but the scattered nature of these convective rains render them insufficient for large scale recharge for the most part. With even drier conditions expected in the next 1-3 months due to the developing El Niño, there is the potential for drought conditions to re-emerge.

Over Florida, the summer rainy season should continue as usual. In general, the second half of the season is a little drier than the first half in south Florida, but more rainfall hits north Florida and the Panhandle. Any drying impacts from El Niño at this time should not greatly offset the summer accumulation of rain. Also, expect Gulf coastal areas to receive more frequent thunderstorms, as Gulf water temperatures are now warm enough to support nocturnal convection.

The recent heavy rains across North Florida, South Alabama, and South Georgia have saturated soils and filled area lakes, ponds, and rivers. This should provide sufficient moisture for planting field crops and greening of pastures for the next month or more. Standing water or saturated soils could hinder field preparations.The tropical season greatly affects rainfall amounts and coverage during late summer and fall in the Southeast. One or more tropical systems, whether a hurricanes, weak storms, or depressions, can bring beneficial rainfall that is a normal component of the climate. Tropical storm Faye brought torrential rainfall to the state of Florida last year and beneficial rains to Georgia and Alabama. El Niño lessens tropical activity in the Atlantic, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico, so the threat of hurricanes or damaging tropical storms should be lower through the remainder of the season.

Looking ahead to the fall/winter. Once we shift seasons into the colder months, the more widely recognized impacts of El Niño in the Southeast begin to set in. Starting in November, El Niño affects the jet stream pattern in a manner that leads to frequent winter storms and frontal systems, cooler temperatures, cloudier skies, and much above average rainfall. In December through March El Niño typically leads to rainfall 40% to 50% greater than normal over the peninsula of Florida and up to 30% greater than normal over coastal Alabama, South Georgia, and coastal North and South Carolina. These winter impacts of El Niño are generally stronger than any other time of year and more consistent among past El Niño events; therefore the winter forecast can be viewed as more reliable.

For more detailed information on El Niño climate shifts in your particular county, please refer to the Climate Risk Tool at AgClimate: