CONTACT: David F. Zierden, State Climatologist of Florida

(850) 644-3417;

March 14, 2014

Download report in PDF format  or read the report below

or read the report below

Outlook Summary

- Early spring should bring variable weather patterns, as we have experienced this winter. There is no tendency towards wetter and cooler or warmer and drier with neutral conditions in the Pacific.

- Summer may bring normal to above normal rainfall, but seasonal predictions for the summer are difficult and have low confidence.

- There is a greater than 50% chance the Pacific Ocean transitions to El Niño during the summer.

- A developing El Niño would mean a less active Atlantic hurricane season.

- A very wet summer followed by near normal winter rainfall and recharge has surface water, groundwater, and soil moisture in good shape going into spring and summer.

- Florida wildfire season has been relatively quite thus far. As long as summer rains begin on time, an active season is not anticipated.

Recent conditions - record setting summer rainfall followed by a near normal winter

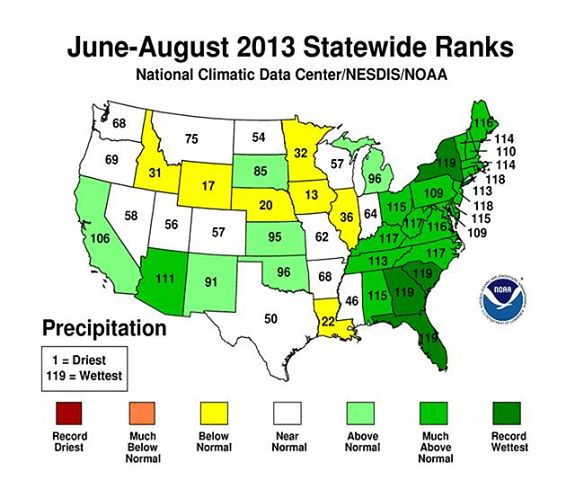

After a summer of record-setting rainfall across much of the Southeast and near-normal winter rainfall, surface water, groundwater, and soil moisture are all in good shape as spring approaches. The States of Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina all experienced the wettest summer on record (since 1895) and many others were in the top five or top ten. The map below shows statewide precipitation rankings since 1895. Cold season rainfall was close to normal, with some locations like south Georgia and northwest Alabama being a little on the dry side, with other locations being a little wet. Overall, winter rainfall was close to normal and provided sufficient recharge of surface water, groundwater, and soil moisture.

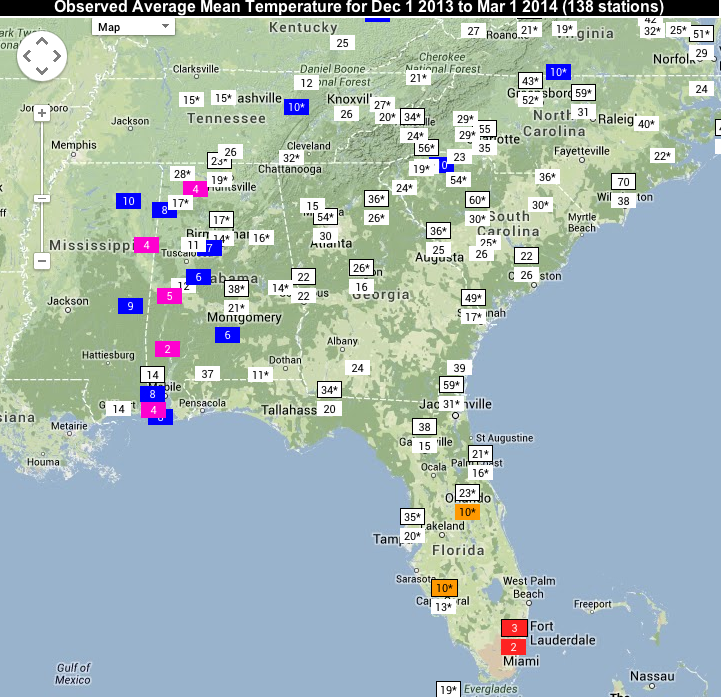

While our neighbors to the north in the Midwest and Northeast experienced a rather severe winter with cold temperatures and frequent snowstorms, temperatures in the Southeast were not too unusual. The snow and ice storms that impacted the Southeast on January 29th and February 13th made it seem like a severe winter, but historical temperature rankings indicate a mixed bag. Some weather stations in western Alabama ranked among the top five or top ten coldest, while south Florida ranked as 2nd or 3rd warmest. In between temperatures were close to normal. Florida citrus, fruit, and vegetable growers did not endure a damaging freeze this year.

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, the Southeast remains relatively drought-free as spring approaches. There are a few spots of D0 (unusually dry) in Alabama and Georgia where they missed some of the winter rain, but D0 does not indicate any drought impact, just areas to watch closely. So far the state of Florida has had a fairly quiet wildfire season, but the peak of the season has not arrived yet. Keetch-Byram Drought Index values range from very moist across north Florida and the Panhandle to over 500 in South Florida. However, high values occur in south Florida every year at this time due to the prolonged dry season.

(click on the header to expand)Pacific Ocean to remain neutral through spring of 2014, possible El Niño this summer

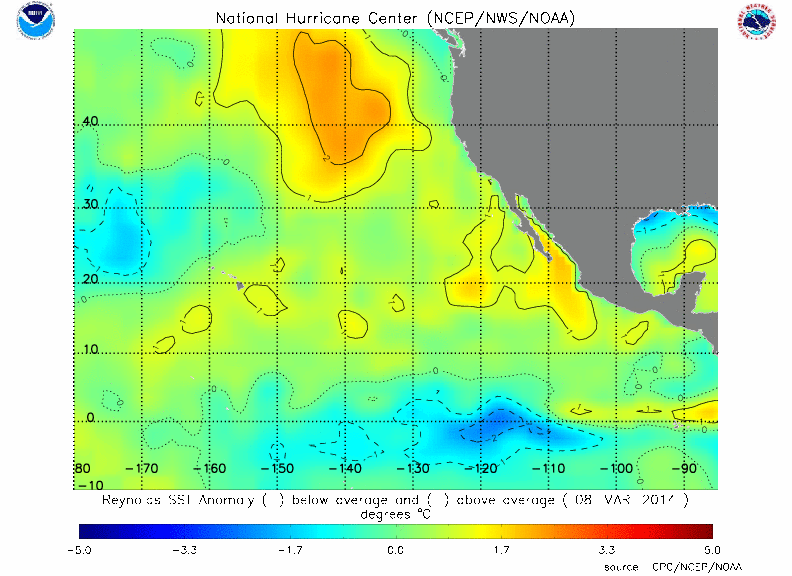

Sea surface temperatures along the equator near the coast of South America cooled slightly in recent weeks, yet remained well within the "normal" range. Near normal sea surface temperatures in this area of the Pacific is known as Neutral conditions. Historically, neutral conditions occur roughly half the years while El Niño and La Niña each occur about a quarter of the time. Neutral conditions have prevailed since April of 2012, including last fall, winter, and spring, giving us two "neutral" years in a row. Neutral conditions will continue at least for the next several months.

Current East Pacific SST Anomaly Analysis (degrees C)

The Pacific Ocean may be in a period of transition right now. Since late December, westerly wind anomalies have been present on and off in the western Pacific along the equator. It is these changes in the trade winds that excite Kelvin waves, which travel eastward to the South American Coast and begin the warming process of surface waters. A very strong Kelvin wave is making its month long trek across the Pacific Ocean right now. In addition, many of the models that predict sea surface temperatures are now forecasting the development of El Niño over the summer. Because of the recent events in the Pacific and the prediction models, NOAA has now issued an El Niño watch, meaning there is a greater that 50% chance of El Niño developing this summer. However, this is a notoriously difficult time of the year to predict the Pacific Ocean, and it takes more than one Kelvin wave to build a full-blown El Niño. We will have to wait and see how the next few months unfold before we know with any certainty that El Niño is on the way.

Rainfall and temperature patterns more variable this spring

Weather patterns for the early spring are prone to be more variable, with swings between warmer, colder, wetter, and drier periods throughout the season. The reason is that the Pacific Ocean is currently in the neutral phase; meaning sea surface temperatures near the equator in eastern and central Pacific Ocean are close to normal. Winter and spring weather and climate patterns in Florida and the Southeast are heavily influenced by the El Niño/La Niña cycle, where ocean temperatures in the tropical Pacific swing between warmer than normal and colder than normal every 2 to 7 years.

With neither El Niño nor La Niña in place this year, the jet streams are freer to meander over North America, leading to greater variability in temperature and rainfall from week to week. When looking at the winter and spring as a whole, the seasonal temperature and rainfall is likely to be close to normal. Instead of the odds being heavily tipped towards wetter and colder or drier and warmer, all possibilities are equally likely in a neutral spring.

Summer climate patterns difficult to predict

While the El Niño/La Niña cycle gives us a good deal of predictability in the cold months, its impact on our summer climate is much weaker. One reason that there is not much of an ENSO signal in the Southeast is that the sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies in the tropical Pacific are usually weaker or in transition during the summer months. But, even when stronger anomalies exist (even stronger than the 0.5 degree El Nino/La Nina threshold), the coupling with the atmosphere is also much weaker during the summer.

Our conceptual model is that El Niño /La Niña cause preferred jet stream patterns over North America. In the winter, the jet stream is more active and farther south and more of a direct driver of storm tracks and climate and weather patterns. In the summer, the jet stream retreats much farther north where 1) it is less affected by the tropical Pacific, and 2) less of player in our weather patterns here in the southeast.

Last summer, the Pacific Ocean was firmly in the neutral phase and we ended up with one of the wettest summers on record. This unusually wet pattern could not have been predicted by looking at the Pacific Ocean and was not predicted by NOAA's climate prediction center.

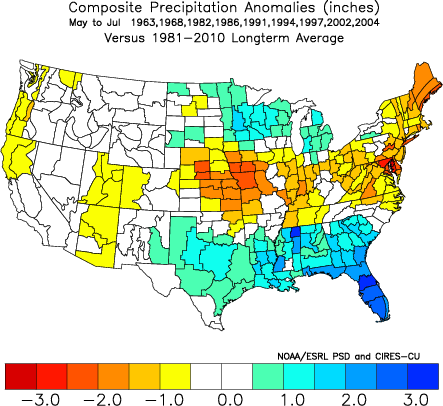

With all of that being said, rainfall patterns may be normal to above normal this summer whether or not the Pacific Ocean transitions into El Nino. The map below shows summer (June through August) rainfall departures from normal in years where there was a transition from neutral to El Niño. On average during these years May through July have been wetter than normal for much of the Southeast. However, these kind of composites or analogs have to be taken with a grain of salt because one or two unusual years can greatly influence the results.

Summer temperatures are highly correlated with rainfall across the Southeast. Frequent rainfall and cloud cover (like last summer) will keep temperatures below normal. Dry clear days are when we see higher afternoon temperatures. Temperatures across the region the last two summers have generally been below normal, corresponding to above normal rainfall.

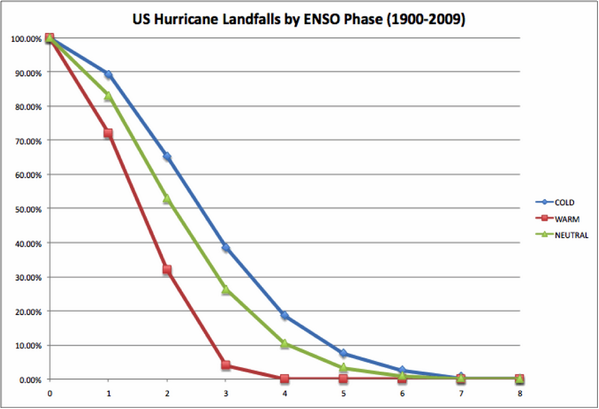

Hurricane season could be impacted by El Niño

If El Niño does develop as forecast this summer, one of the first impacts could be on the Atlantic hurricane season. It is well-known that El Niño tends to suppress hurricane formation in the Atlantic basin by creating an environment of unfavorable vertical sheer, or winds changing with height. Sheer will tear a developing storm apart before it has a chance to grow into a strong hurricane. If an El Niño forms, look for fewer hurricanes this year. Keep in mind that landfall from a hurricane or destructive tropical system is still possible, even in relatively quiet years, and that plans should be ready every year to deal with a possible storm. The figure below shows the probability of hurricane landfalls in the three phases of the Pacific Ocean. The probability of two or more hurricanes making landfall in the United States is only half as great during El Niño as with the other phases.