From AgroClimate.

Date updated: November 13, 2009

El Niño in charge in the Pacific Ocean

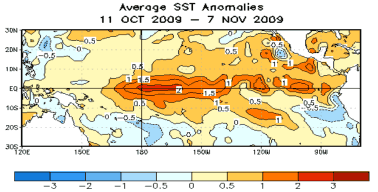

The Pacific Ocean is firmly entrenched in the El Niño Phase. Ocean temperatures over the past few months have continued to warm in the eastern and central tropical Pacific Ocean and are now over 1.0 degree C warmer than normal over a large area. Sea surface temperatures in this region of 0.5 degree C warmer than normal are the commonly used threshold to designate El Niño conditions. El Niño refers to a periodic (every 2-7 years) warming of the tropical Pacific Ocean along the equator from the coast of South America to the central Pacific. Once surface temperatures warm to over 1.0 degrees C the El Niño is considered moderate in strength (the three classifications are weak, moderate, and strong). This warming began in May and has continued through the summer and fall months. The development of this El Niño follows the typical life cycle of building in the summer and fall months before reaching peak strength in mid winter.

Sea surface temperature departures from normal (degrees C) over The Pacific Ocean as of July 1 (courtesy NOAA).

Modeling centers around the world that predict El Niño/La Niña agree that waters will continue to warm and result in at least a moderate El Niño during the winter and spring months. There is a small chance that the El Niño will reach the strong category. There is no chance of La Niña returning in the near future and very little chance of neutral conditions.

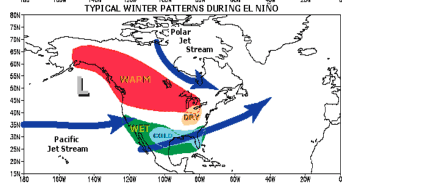

El Niño brings excess rain and storminess to parts of the Southeast. Normally beginning in November, El Niño affects the jet stream pattern in a manner that leads to frequent winter storms and frontal systems, cooler temperatures, cloudier skies, and much above average rainfall. Winter storms tend to develop along the Pacific jet stream and track into California. From there, the disturbances often slide along the Southern U.S., where the low pressure systems can tap moisture from the Gulf of Mexico and reintensify as they track along the northern Gulf Coast and up the Southeast Atlantic. The result is frequent winter storm passages, increased rainfall and cooler temperatures over much of the Southeast.

Typical winter jet stream patterns associated with El Niño (courtesy NOAA).

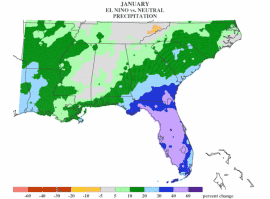

In December through March El Niño typically leads to rainfall 40% to 50% greater than normal over the peninsula of Florida and up to 30% greater than normal over coastal Alabama, South Georgia, and coastal North and South Carolina. El Niño's influence is especially strong in the southern two-thirds of the state. The mountainous region of north Alabama, North Georgia and middle and east Tennessee is a transition zone. Depending on where the transition zone occurs this winter, the mountains will experience drier-than-normal, near-normal or wetter-than-normal conditions. These winter impacts of El Niño are generally stronger than any other time of year and more consistent among past El Niño events; therefore the winter forecast can be viewed as the most reliable compared to other times of the year.

Average changes in precipitation (percent change from normal) for August during El Niño episodes

Increase risk of flooding across most of the Southeast. With soils already near saturation from September and October rains, exacerbated by tropical storm Ida, the risk of flooding is expected to remain higher than normal through the winter. Many streams that are usually at their lowest flows during October are at levels normally seen in March, which is the month that generally has the highest flows. Since the soils are already near saturation and stream flows high, the potential for flooding this winter is higher than normal. The peninsula of Florida has not seen such plentiful rains and remains drier than normal.

Cooler temperatures expected, but not necessarily severe freezes. In addition to the increased rain and storminess, El Niño is also associated with cooler winter temperatures over the entire Southeast. Winter temperatures generally run from 2 to 4 degrees F cooler than normal during El Niño winters. The greater number of cloudy and rainy days are primarily responsible for the cooler temperatures, as the change is seen more in afternoon high temperatures rather than morning lows. The cooler temperatures lead to greater accumulation of chill hours, which are necessary for proper reproduction and fruit setting for flowering fruits such as peaches, blueberries, and strawberries.

While El Niño is know to bring cooler temperatures, the risk of extreme cold weather or damaging freezes is actually lower than normal. We believe that the same jet stream patterns that lead to frequent storminess also tend to "block" the intrusions of frigid arctic air masses that usher in extreme low temperatures. Of the dozen or more catastrophic freezes to hit the Southeast in the last century or more, almost all happened when the Pacific Ocean temperatures were in the neutral range rather than El Niño or La Niña.

Increased risk of severe weather over Florida. Bart Hagemeyer, meteorologist in charge of the National Weather Service Forecast Office in Melbourne, FL, has demonstrated a clear connection between El Niño and winter tornado outbreaks in Central Florida. Once again tied to changes in the jet stream patterns, El Niño creates an environment of higher upper-level winds and increased vertical shear (winds changing direction with height), conditions which are necessary for the development of strong and long path tornadoes. The two of the deadliest tornado outbreaks in the history of Florida (February 1998 - 42 dead, February 2007 - 21 dead) both occurred during El Niño winters.

For more detailed information on El Niño climate shifts in your particular county, please refer to the Climate Risk Tool at AgClimate: